In this series, I’m compiling some of the quips and one-liners that I’ll use with my students to hopefully make my lessons more memorable for them.

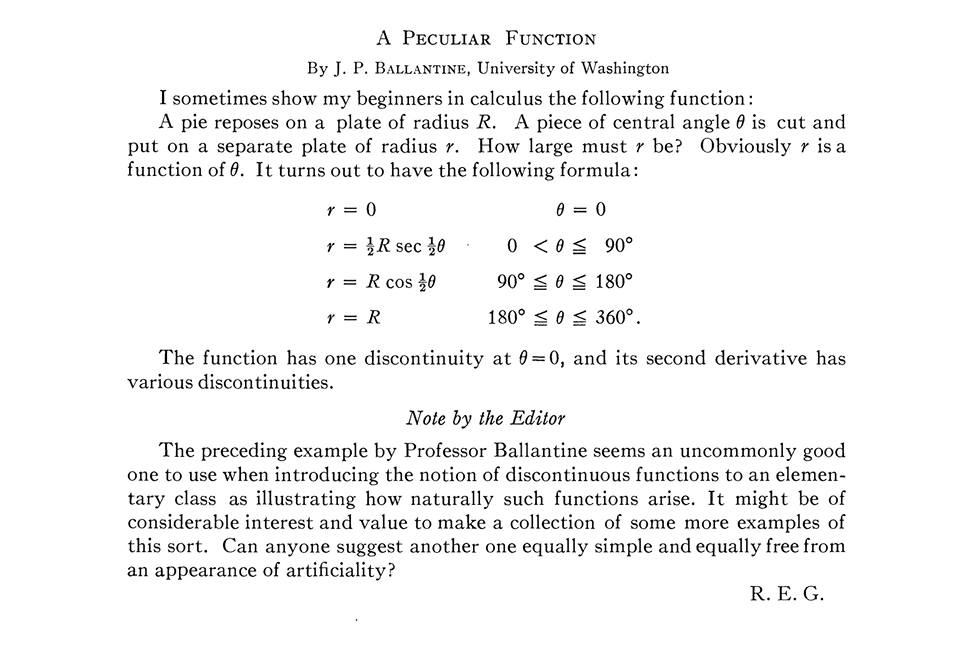

Here’s a problem from calculus:

Let . Find

.

We begin by finding the first derivative using the Product Rule:

.

Next, we apply the Product Rule again to find the second derivative:

.

At this point, before simplifying to get the final answer, I’ll ask my students why the term appears twice. After a moment, somebody will usually volunteer the answer: the first term came from differentiating

first and then

second, while the other term came from differentiating

first and then

second. Either way, we end up with the same term.

I then tell my class that there’s a technical term for this: Oops, I did it again.

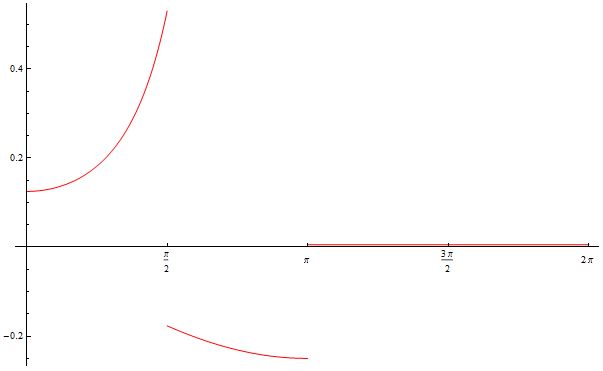

While on the topic, I can’t resist also sharing this (a few years ago, this was shown on the JumboTron of Dallas Mavericks games during timeouts):