In this series of posts, I explore properties of complex numbers that explain some surprising answers to exponential and logarithmic problems using a calculator (see video at the bottom of this post). These posts form the basis for a sequence of lectures given to my future secondary teachers.

To begin, we recall that the trigonometric form of a complex number is

where and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant. As noted before, this is analogous to converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

There’s a shorthand notation for the right-hand side () that I’ll justify later in this series.

This post builds off the previous two posts by completing the proof of De Moivre’s Theorem.

Theorem. If is an integer, then

.

The proof has two parts:

- For

: proof by induction.

- For

: let

, and then use part 1.

In the previous post, I presented how I describe the proof of step 1 to students. Today, I’ll discuss how I present step 2.

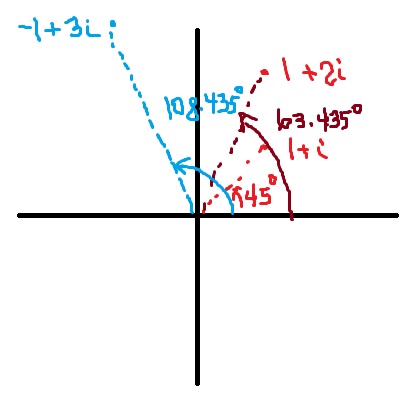

My personal opinion is that the proof of step 2 goes easiest when a numerical example is done first. Let . Students can usually volunteer the successive steps of this special case:

At this point, students usually want to multiply by the conjugate of the denominator. There’s nothing wrong with doing that, of course, but it’s more elegant to write the numerator in trigonometric form:

,

which matches what we would have expected. Students are now prepared for the proof, which I try to place alongside the above computation for .

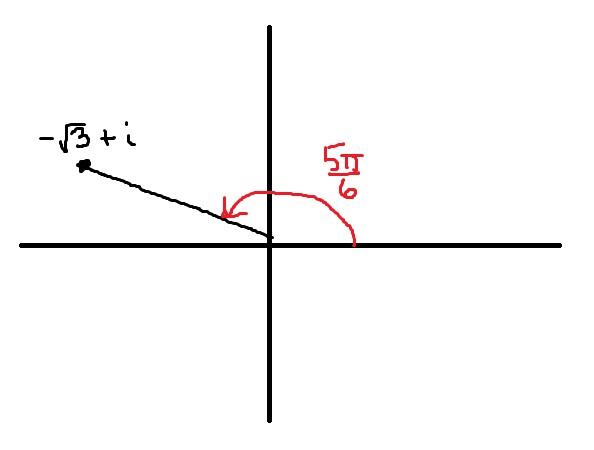

Proof for . Let

. I tell students to imagine that

is

, so that

is equal to (students volunteer)

. In other words,

is negative and

is positive. Then

I again remind everyone that is positive, and so (like a good MIT freshman) the previous work applies:

The remaining steps mirror the calculation above:

,

thus ending the proof.

For completeness, here’s the movie that I use to engage my students when I begin this sequence of lectures.