Recently, I announced that my paper Parabolic Properties from Pieces of String had been published in the magazine Math Horizons. The article had multiple aims; in chronological order of when I first started thinking about them:

- Prove that string art from two line segments traces a parabola.

- Prove that a quadratic polynomial satisfies the focus-directrix property of a parabola, which is the reverse of the usual logic when students learn conic sections.

- Prove the reflective property of parabolas.

- Accomplish all of the above without using calculus.

While I’m generally pleased with the final form of the article, the necessity of publication constraints somewhat abbreviated the original goal of this project: determining a pedagogically sound way of convincing a bright Algebra I student that string art unexpectedly produces a parabola. While all the necessary mathematics is in the article, I think the article is somewhat lacking on how to sell the idea to students. So, in this series of posts, I’d like to expand on the article with some pedagogical thoughts about connecting string art to parabolas.

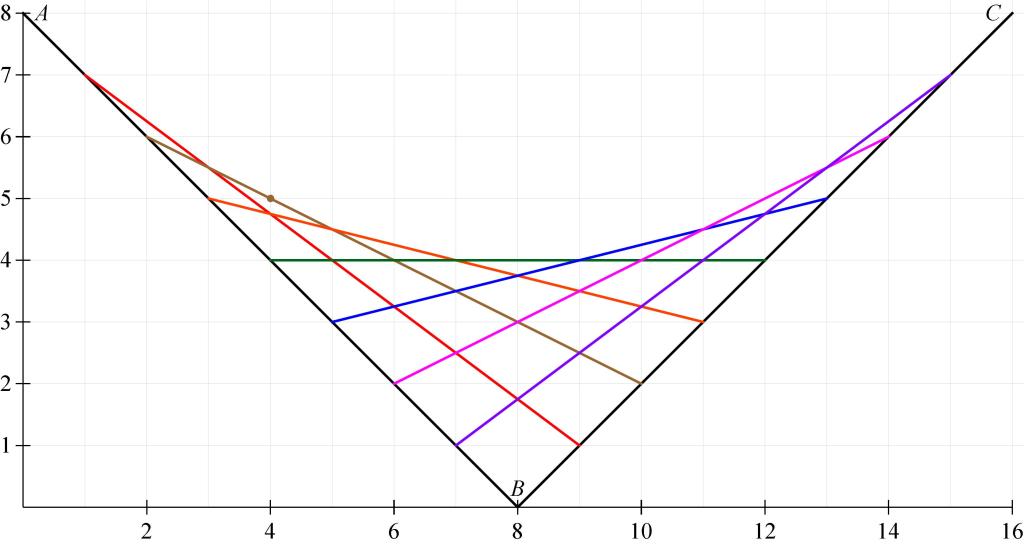

As discussed in the previous post, we begin our explorations with string art connecting evenly spaced points on line segments and

with endpoints

,

, and

. We will call these colored line segments “strings.”

We now ask the following two questions:

- For each of $x = 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12,$ and

, which string has the largest

coordinate?

- For each of these values of

, what is the value of this largest

coordinate?

Evidently, for , the brown string that connects

to

has the largest

coordinate. This point is marked with the small brown circle. From the lines on the graph paper, it appears that this brown point is

.

For , the horizontal green string appears to have the largest

coordinate, and clearly that point is

.

For , the pink string that connects

to

has the largest

coordinate. From the lines on the graph paper, it appears that this point is

.

Unfortunately, for ,

,

, and

, it’s evident which string has the largest

coordinate, but it’s not so easy to confidently read off its value. For this example, this could be solved by using finer graph paper with marks at each quarter (instead of at the integers). However, it’s far better to actually use the point-slope formula to find the equation of the colored line segments.

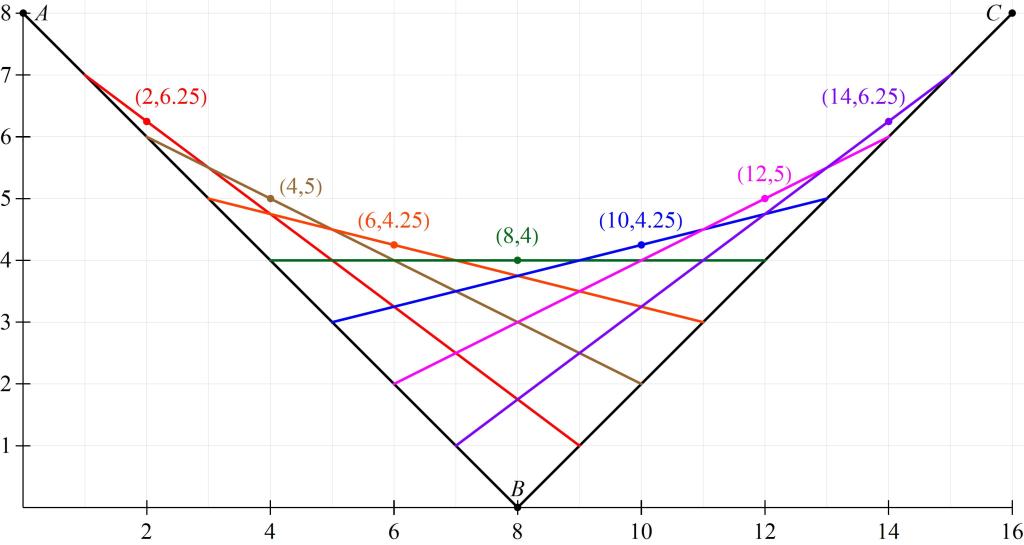

For example, for , the red string has the largest

coordinate. This string connects the points

and

, and so the slope of this string is

. Using the point-slope form of a line, the equation of the red string is thus

Substituting , the

coordinate of the highest string at

is

.

Similarly, at , the equation of the orange string turns out to be

, and the

coordinate of the highest string at

is

.

At , the equation of the blue string is

, and the

coordinate of the highest string at

is

.

Finally, at , the equation of the purple string is

, and the

coordinate of the highest string at

is

.

The interested student could confirm the values for ,

, and

that were found earlier by just looking at the picture.

We now add the coordinates of these points to the picture.

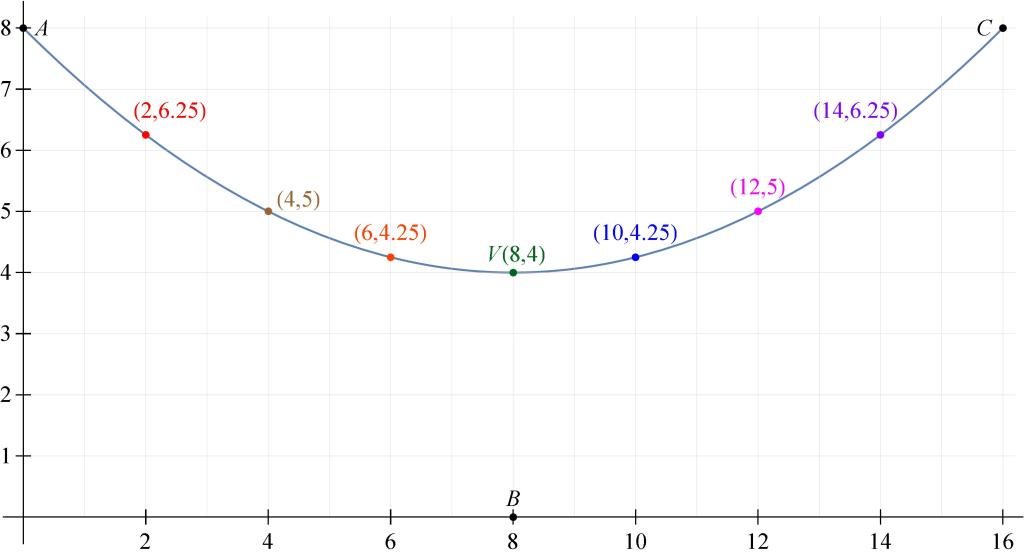

However, perhaps it’s clearer to plot these points on a separate graph, without the clutter of the strings:

These points are definitely following some kind of curve. In the next post in this series, I’ll discuss a way of convincing students that the curve is actually a parabola.