Sadly, at least at my university, Taylor series is the topic that is least retained by students years after taking Calculus II. They can remember the rules for integration and differentiation, but their command of Taylor series seems to slip through the cracks. In my opinion, the reason for this lack of retention is completely understandable from a student’s perspective: Taylor series is usually the last topic covered in a semester, and so students learn them quickly for the final and quickly forget about them as soon as the final is over.

Of course, when I need to use Taylor series in an advanced course but my students have completely forgotten this prerequisite knowledge, I have to get them up to speed as soon as possible. Here’s the sequence that I use to accomplish this task. Covering this sequence usually takes me about 30 minutes of class time.

I should emphasize that I present this sequence in an inquiry-based format: I ask leading questions of my students so that the answers of my students are driving the lecture. In other words, I don’t ask my students to simply take dictation. It’s a little hard to describe a question-and-answer format in a blog, but I’ll attempt to do this below.

In the previous posts, I described how I lead students to the definition of the Maclaurin series

,

,

which converges to  within some radius of convergence for all functions that commonly appear in the secondary mathematics curriculum.

within some radius of convergence for all functions that commonly appear in the secondary mathematics curriculum.

Step 7. Let’s now turn to trigonometric functions, starting with  .

.

What’s  ? Plugging in, we find

? Plugging in, we find  .

.

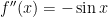

As before, we continue until we find a pattern. Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

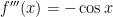

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

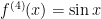

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

No pattern yet. Let’s keep going.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

OK, it looks like we have a pattern… albeit more awkward than the patterns for  and

and  . Plugging into the series, we find that

. Plugging into the series, we find that

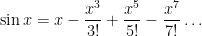

If we stare at the pattern of terms long enough, we can write this more succinctly as

The  term accounts for the alternating signs (starting on positive with

term accounts for the alternating signs (starting on positive with  ), while the

), while the  is needed to ensure that each exponent and factorial is odd.

is needed to ensure that each exponent and factorial is odd.

Let’s see…  has a Taylor expansion that only has odd exponents. In what other sense are the words “sine” and “odd” associated?

has a Taylor expansion that only has odd exponents. In what other sense are the words “sine” and “odd” associated?

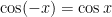

In Precalculus, a function  is called odd if

is called odd if  for all numbers

for all numbers  . For example,

. For example,  is odd since

is odd since  since 9 is a (you guessed it) an odd number. Also,

since 9 is a (you guessed it) an odd number. Also,  , and so

, and so  is also an odd function. So we shouldn’t be that surprised to see only odd exponents in the Taylor expansion of

is also an odd function. So we shouldn’t be that surprised to see only odd exponents in the Taylor expansion of  .

.

A pedagogical note: In my opinion, it’s better (for review purposes) to avoid the  notation and simply use the “dot, dot, dot” expression instead. The point of this exercise is to review a topic that’s been long forgotten so that these Taylor series can be used for other purposes. My experience is that the

notation and simply use the “dot, dot, dot” expression instead. The point of this exercise is to review a topic that’s been long forgotten so that these Taylor series can be used for other purposes. My experience is that the  adds a layer of abstraction that students don’t need to overcome for the time being.

adds a layer of abstraction that students don’t need to overcome for the time being.

Step 8. Let’s now turn try  .

.

What’s  ? Plugging in, we find

? Plugging in, we find  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

It looks like the same pattern of numbers as above, except shifted by one derivative. Let’s keep going.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

Next,  , so that

, so that  .

.

OK, it looks like we have a pattern somewhat similar to that of $\sin x$, except only involving the even terms. I guess that shouldn’t be surprising since, from precalculus we know that  is an even function since

is an even function since  for all

for all  .

.

Plugging into the series, we find that

If we stare at the pattern of terms long enough, we can write this more succinctly as

As we saw with  , the above series converge quickest for values of

, the above series converge quickest for values of  near

near  . In the case of

. In the case of  and

and  , this may be facilitated through the use of trigonometric identities, thus accelerating convergence.

, this may be facilitated through the use of trigonometric identities, thus accelerating convergence.

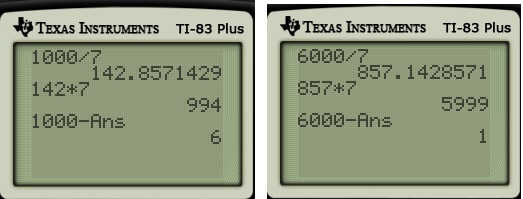

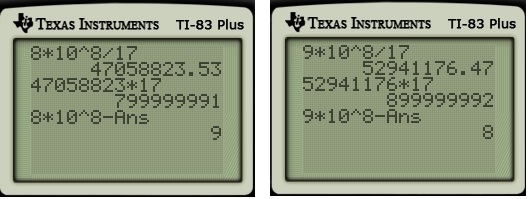

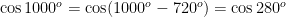

For example, the series for  will converge quite slowly (after converting

will converge quite slowly (after converting  into radians). However, we know that

into radians). However, we know that

using the periodicity of  . Next, since $\latex 280^o$ is in the fourth quadrant, we can use the reference angle to find an equivalent angle in the first quadrant:

. Next, since $\latex 280^o$ is in the fourth quadrant, we can use the reference angle to find an equivalent angle in the first quadrant:

Finally, using the cofunction identity  , we find

, we find

.

.

In this way, the sine or cosine of any angle can be reduced to the sine or cosine of some angle between  and $45^o = \pi/4$ radians. Since

and $45^o = \pi/4$ radians. Since  , the above power series will converge reasonably rapidly.

, the above power series will converge reasonably rapidly.

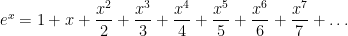

Step 10. For the final part of this review, let’s take a second look at the Taylor series

Just to be silly — for no apparent reason whatsoever, let’s replace  by

by  and see what happens:

and see what happens:

![e^{ix} = \displaystyle 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \frac{x^6}{6!} \dots + i \left[\displaystyle x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!} \dots \right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=e%5E%7Bix%7D+%3D+%5Cdisplaystyle+1+-+%5Cfrac%7Bx%5E2%7D%7B2%21%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7Bx%5E4%7D%7B4%21%7D+-+%5Cfrac%7Bx%5E6%7D%7B6%21%7D+%5Cdots+%2B+i+%5Cleft%5B%5Cdisplaystyle+x+-+%5Cfrac%7Bx%5E3%7D%7B3%21%7D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7Bx%5E5%7D%7B5%21%7D+-+%5Cfrac%7Bx%5E7%7D%7B7%21%7D+%5Cdots+%5Cright%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

after separating the terms that do and don’t have an  .

.

Hmmmm… looks familiar….

So it makes sense to define

,

,

which is called Euler’s formula, thus proving an unexpected connected between  and the trigonometric functions.

and the trigonometric functions.

of a triangle is

and

and the measure of angle

— are known.

is an altitude for

, then

is a right triangle. Therefore,

, or

.

.

An important consequence of the SAS area formula is the Law of Sines. Since all three formulas must give the same area

An important consequence of the SAS area formula is the Law of Sines. Since all three formulas must give the same area , we have

produces the Law of Sines:

Case 2: ASA. Now suppose that we are given the measures of two angles and the length of the side in between them — say, angles

Case 2: ASA. Now suppose that we are given the measures of two angles and the length of the side in between them — say, angles and

and side

. Naturally, we can also get the measure of angle

since the sum of the measures of the three angles must be

.

and