In this series, I’m compiling some of the quips and one-liners that I’ll use with my students to hopefully make my lessons more memorable for them. Today’s quip is one that I’ll use when simple techniques get used in a complicated way.

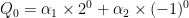

Consider the solution of the linear recurrence relation

,

,

where  and

and  . With no modesty, I call this one the Quintanilla sequence when I teach my students — the forgotten little brother of the Fibonacci sequence.

. With no modesty, I call this one the Quintanilla sequence when I teach my students — the forgotten little brother of the Fibonacci sequence.

To find the solution of this linear recurrence relation, the standard technique — which is a pretty long procedure — is to first solve the characteristic equation, from  , we obtain the characteristic equation

, we obtain the characteristic equation

This can be solved by any standard technique at a student’s disposal. If necessary, the quadratic equation can be used. However, for this one, the left-hand side simply factors:

(Indeed, I “developed” the Quintanilla equation on purpose, for pedagogical reasons, because its characteristic equation has two fairly simple roots — unlike the characteristic equation for the Fibonacci sequence.)

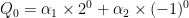

From these two roots, we can write down the general solution for the linear recurrence relation:

,

,

where  and

and  are constants to be determined. To find these constants, we plug in

are constants to be determined. To find these constants, we plug in  :

:

.

.

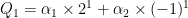

To find these constants, we plug in  :

:

.

.

We then plug in  :

:

.

.

Using the initial conditions gives

This is a system of two equations in two unknowns, which can then be solved using any standard technique at the student’s disposal. Students should quickly find that  and

and  , so that

, so that

,

,

which is the final answer.

Although this is a long procedure, the key steps are actually first taught in Algebra I: solving a quadratic equation and solving a system of two linear equations in two unknowns. So here’s my one-liner to describe this procedure:

This is just an algebra problem on steroids.

Yes, it’s only high school algebra, but used in a creative way that isn’t ordinarily taught when students first learn algebra.

I’ll use this “on steroids” line in any class when a simple technique is used in an unusual — and usually laborious — way to solve a new problem at the post-secondary level.

be an integer. Then

is odd if and only if

is odd.” I’ll ask my students, “What is the structure of this proof?”

is odd, and show that

is odd.

is odd, and show that

is odd.

with real coefficients has a complex root

, then

is also a root. It’s a blue-light special: two for the price of one.