Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprisingly depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received:

What is the chance of winning a game of BINGO after only four turns?

When my class posed this question, I was a little concerned that the getting the answer might be beyond the current abilities of a gifted elementary student. As discussed over the past couple of posts, for a non-standard BINGO game with 44 numbers, the answer is

After we got the answer, I then was asked the question that I had fully anticipated but utterly dreaded:

What’s that in decimal?

With these gifted students, I encourage thinking as much as possible without a calculator… and they wanted me to provide the answer to this one in like fashion. For my class, this actually did serve a purpose by illustrating a really complicated long division problem so they could reminded about the number of leading zeroes in such a problem.

Gritting my teeth, I started on the answer:

At this point, I was asked the other question that I had anticipated but utterly dreaded… motivated by child-like curiosity mixed perhaps with a touch of sadism:

At this point, I was asked the other question that I had anticipated but utterly dreaded… motivated by child-like curiosity mixed perhaps with a touch of sadism:

How long do we have before the digits start repeating?

My stomach immediately started churning.

I told the class that I’d have to figure this one later. But I told them that the answer would definitely be less than 135,751 times. My class was surprised that I could even provide this level of (extremely) modest upper limit on the answer. After some prompting, my class saw the reasoning for this answer: there are only 135,751 possible remainders after performing the subtraction step in the division algorithm, and so a remainder has to be repeated after 135,751 steps. Therefore, the digits will start repeating in 135,751 steps or less.

What I knew — but probably couldn’t explain to these elementary-school students, and so I had to work this out for myself and then get back to them with the answer — is that the length of the repeating block  is the least integer so that

is the least integer so that

which is another way of saying that we’ve used the division algorithm enough times so that a remainder repeats. Written in the language of group theory,  is the least integer that satisfies

is the least integer that satisfies

(A caveat:this rule works because neither 2 nor 5 is a factor of 135,751… otherwise, those factors would have to be taken out first.)

Some elementary group theory can now be used to guess the value of  . Let

. Let  be the multiplicative group of integers modulo

be the multiplicative group of integers modulo  which are relatively prime which. The order of this group is denoted by

which are relatively prime which. The order of this group is denoted by  , called the Euler totient function. In general, if

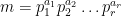

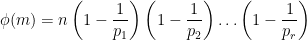

, called the Euler totient function. In general, if  is the prime factorization of

is the prime factorization of  , then

, then

For the case at hand, the prime factorization of  can be recovered by examining the product of the fractions near the top of this post:

can be recovered by examining the product of the fractions near the top of this post:

Therefore,

Next, there’s a theorem from group theory that says that the order  of an element of a group must be a factor of the order of the group. In other words, the number

of an element of a group must be a factor of the order of the group. In other words, the number  that we’re seeking must be a factor of

that we’re seeking must be a factor of  . This is easy to factor:

. This is easy to factor:

Therefore, the number  has the form

has the form

,

,

where  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are integers.

are integers.

So, to summarize, we can say definitively that  is at most

is at most  , and that were have narrowed down the possible values of

, and that were have narrowed down the possible values of  to only

to only  possibilities (the product of one more than all of the exponents). So that’s a definite improvement and reduction from my original answer of

possibilities (the product of one more than all of the exponents). So that’s a definite improvement and reduction from my original answer of  possibilities.

possibilities.

At this point, there’s nothing left to do except test all 126 possibilities. Unfortunately, there’s no shortcut to this; it has to be done by trial and error. Thankfully, this can be done with Mathematica:

The final line shows that the least such value of

The final line shows that the least such value of  is 210. Therefore, the decimal will repeat after 210 digits. So here are the first 210 digits of

is 210. Therefore, the decimal will repeat after 210 digits. So here are the first 210 digits of  (courtesy of Mathematica):

(courtesy of Mathematica):

0.000029465712959757202525211600651192256410634175807176374391348866675015285338597874048809953517837805983013016478699972744215512224587664\

179269397647162820163387378361853688002298325610861061796966504850792996…

For more on this, see https://meangreenmath.com/2013/08/23/thoughts-on-17-and-other-rational-numbers-part-6/ and https://meangreenmath.com/2013/08/25/thoughts-on-17-and-other-rational-numbers-part-8/.