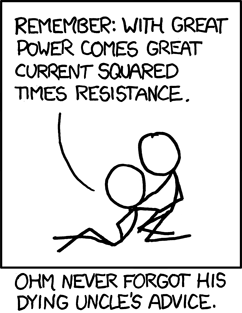

I wish I had the talent to do something like this.

Category: Physics

Ohm

Source: http://www.xkcd.com/643/

Source: http://www.xkcd.com/643/

Engaging students: Vectors in two dimensions

In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Derek Skipworth. His topic, from Precalculus: vectors in two dimensions.

A. How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

While it may be a cop-out to use this example since I am developing it for an actual lesson plan, I will go ahead and use it because I feel it is a strong activity. I am developing a series of 21 problems that will be the base for forming the students’ treasure maps. There will be three jobs: Cartographer, the map maker; Lie Detector, who checks for orthogonality; and Calculator, who will solve the vector problems. The 21 problems will be broken down into 7 per page, and the students will switch jobs after each page. The rule is that any vectors that are orthogonal with each other cannot be included in your map. There are three of these on each page, so each group should end up with a total of 12 vectors on their map. Once orthogonality is checked by the Lie Detector, the Calculator will do the expressed operations on the vector pairs to come up with the vector to be drawn. The map maker will then draw the vector, as well as the object the vector leads to. Each group will have their directions in different orders so that every group has their own unique map. The idea is for the students to realize (if they checked orthogonality correctly) that, even though every map is different, the sum of all vectors still leads you to the same place, regardless of order.

B. How does this topic extend what your students should have learned in previous courses?

Vectors build upon many topics from previous courses. For one, it teaches the student to use the Cartesian plane in a new way than they have done previously. Vectors can be expressed in terms of force in the and

directions, which result in a representation very similar to an ordered pair. It gets expanded to teach the students that unlike an ordered pair, which represents a distinct point in space, a vector pair represents a specific force that can originate from any point on the Cartesian Plane.

Vectors also build on previous knowledge of triangles. When written as , we can find the magnitude of the vector by using the Pythagorean Theorem. It gives them a working example of when this theorem can be applied on objects other than triangles. It also reinforces the students trigonometry skills since the direction of a vector can also be expressed using magnitude and angles.

E. How can technology be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

The PhET website has one of the best tools I’ve seen for basic knowledge of two dimensional vector addition, located at http://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/vector-addition. This is a java-based program that lets you add multiple vectors (shown in red) in any direction or magnitude you want to get the sum of the vectors (shown in green). Also shown at the top of the program is the magnitude and angle of the vector, as well as its corresponding and

values.

What’s great about this program is it puts the power in the student’s hands. They are not forced to draw multiple sets of vectors themselves. Instead, they can quickly throw them in the program and manipulate them without any hassle. This effectively allows the teacher to cover the topic quicker and more effectively due to the decreased amount of time needed to combine all vectors on a graph.

E=mc2

The Visual Patterns of Audio Frequencies Seen through Vibrating Sand

Hat tip to http://www.thisiscolossal.com/2013/06/the-visual-patterns-of-audio-frequencies-seen-through-vibrating-sand/, where I first saw the video below and which posts some details about how this video was made.

Measuring terminal velocity

Using a simultaneously falling softball as a stopwatch, the terminal velocity of a whiffle ball can be obtained to surprisingly high accuracy with only common household equipment. In the January 2013 issue of College Mathematics Monthly, we describe an classroom activity that engages students in this apparently daunting task that nevertheless is tractable, using a simple model and mathematical techniques at their disposal.

Pendulum waves

Courtesy of the physicists at Harvard: pendulum waves. Click here for more information.

Acceleration

The following two questions came from a middle-school math textbook. The first is reasonable, while the second is a classic example of an author being overly cute when writing a homework problem.

- A car slams on its brakes, coming to a complete stop in 4 seconds. The car was traveling north at 60mph. Calculate the acceleration.

- A rocket blasts off. At 10 seconds after blast off, it is at 10,000 feet, traveling at 3600mph. Assuming the direction is up, calculate the acceleration.

For the first question, we’ll assume constant deceleration (after all, this comes from a middle-school textbook). First, let’s convert from miles per hour to feet per second:

The deceleration is therefore equal to the change in velocity over time, or

Now notice the word north in the statement of the first question. This bit of information is irrelevant to the problem. I presume that the writer of the problem wants students to practice picking out the important information of a problem from the unimportant… again, a good skill for students to acquire.

Let’s now turn to the second question. At first blush, this also has irrelevant information… it is at 10,000 feet. So I presume that the author wants students to solve this in exactly the same way:

for an acceleration of

The major flaw with this question is that the acceleration of the rocket completely determines the distance that the rocket travels. While middle-school students would not be expected to know this, we can use calculus to determine the distance. Since the initial position and velocity are zero, we obtain

Therefore, the rocket travels a distance of . In other words, not 10,000 feet.

As a mathematician, this is the kind of error that drives me crazy, as I would presume that the author of this textbook should know that he/she just can’t make up a distance in the effort of making a problem more interesting to students.

Fun with Dimensional Analysis

The principle of diminishing return states that as you continue to increase the amount of stress in your training, you get less benefit from the increase. This is why beginning runners make vast improvements in their fitness and elite runners don’t.

J. Daniels, Daniels’ Running Formula (second edition), p. 13

In February 2013, I began a serious (for me) exercise program so that I could start running 5K races. On March 19, I was able to cover 5K for the first time by alternating a minute of jogging with a minute of walking. My time was 36 minutes flat. Three days later, on March 22, my time was 34:38 by jogging a little more and walking a little less. During that March 22 run, I started thinking about how I could quantify this improvement.

On March 19, my rate of speed was

.

On March 22, my rate of speed was

.

That’s a change of over 3 days (accounting for roundoff error in the last decimal place), and so the average rate of change is

.

By way of comparison, imagine a keg of beer floating in space. The specifications of beer kegs vary from country to country, but I’ll use the U.S. convention that the mass is 72.8 kg and its height is 23.3 inches = 59.182 cm. Also, for ease of calculation, let’s assume that the keg of beer is a uniformly dense sphere with radius 59.182/2 = 29.591 cm. Under this assumption, the acceleration due to gravity near the surface of the sphere is the same as the acceleration 29.591 cm away from a point-mass of 72.8 kg. Using Newton’s Second Law and the Law of Universal Gravitation, we can solve for the acceleration:

,

where is the gravitational constant,

is the mass of the beer keg,

is the distance of a particle from the center of the beer keg,

is the mass of the particle, and

is the acceleration of the particle. Solving for

, we find

.

Since this is only an approximation based on a hypothetical spherical keg of beer, let’s round off and define 1 beerkeg of acceleration to be equal to .

With this new unit, my improvement in speed from March 19 to March 22 can be quantified as

.

I love physics: improvements in physical fitness can be measured in kegs of beer.

I chose the beerkeg as the unit of measurement mostly for comedic effect (I’m personally a teetotaler). If the reader desires to present a non-alcoholic version of this calculation to students, I’m sure that coolers of Gatorade would fit the bill quite nicely.

For what it’s worth, at the time of this writing (June 7), my personal record for a 5K is 26:58, and I’m trying hard to get down to 25 minutes. Alas, my current improvements in fitness have definitely witnessed the law of diminishing return and is probably best measured in millibeerkegs.

Interdisciplinary Studies (Part 1)

An eccentric investor hired a biologist, a mathematician, and a physicist to design and train the perfect racehorse. After studying the problem for a couple of weeks, they returned to the investor to present their results.

The biologist said, “I’ve come up with a plan to breed the perfect racehorse. It’ll just take a thousand or two generations of breeding.”

The mathematician said, “I haven’t been able to solve this problem yet, but I’ve made some preliminary findings. So far, I’ve been able to show that for each horse race there will exist a winner, and furthermore that winner will be unique.”

So the investor’s hopes were pinned on the physicist, who began, “I think I’ve solved this race horse problem, but I had to make a few simplifying assumptions. First, let’s assume that each horse is a perfect frictionless rolling sphere…”