The following problem appeared in Volume 97, Issue 3 (2024) of Mathematics Magazine.

Two points

and

are chosen at random (uniformly) from the interior of a unit circle. What is the probability that the circle whose diameter is segment

lies entirely in the interior of the unit circle?

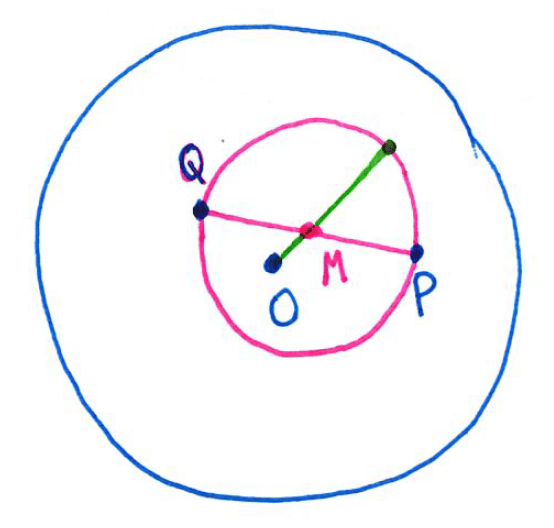

It took me a while to wrap my head around the statement of the problem. In the figure, the points and

are chosen from inside the unit circle (blue). Then the circle (pink) with diameter

has center

, the midpoint of

. Also, the radius of the pink circle is

.

The pink circle will lie entirely the blue circle exactly when the green line containing the origin , the point

, and a radius of the pink circle lies within the blue circle. Said another way, the condition is that the distance

plus the radius of the pink circle is less than 1, or

.

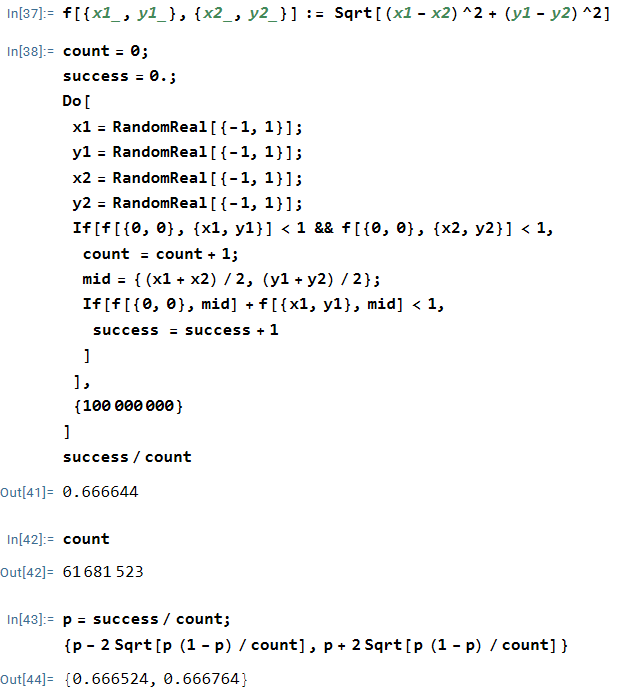

As a first step toward wrapping my head around this problem, I programmed a simple simulation in Mathematica to count the number of times that when points

and

were chosen at random from the unit circle.

In the above simulation, out of about 61,000,000 attempts, 66.6644% of the attempts were successful. This leads to the natural guess that the true probability is . Indeed, the 95% confidence confidence interval

contains

, so that the difference of

from

can be plausibly attributed to chance.

I end with a quick programming note. This certainly isn’t the ideal way to perform the simulation. First, for a fast simulation, I should have programmed in C++ or Python instead of Mathematica. Second, the coordinates of and

are chosen from the unit square, so it’s quite possible for

or

or both to lie outside the unit circle. Indeed, the chance that both

and

lie in the unit disk in this simulation is

, meaning that about

of the simulations were simply wasted. So the only sense that this was a quick simulation was that I could type it quickly in Mathematica and then let the computer churn out a result. (I’ll talk about a better way to perform the simulation in the next post.)