The principle of diminishing return states that as you continue to increase the amount of stress in your training, you get less benefit from the increase. This is why beginning runners make vast improvements in their fitness and elite runners don’t.

J. Daniels, Daniels’ Running Formula (second edition), p. 13

In February 2013, I began a serious (for me) exercise program so that I could start running 5K races. On March 19, I was able to cover 5K for the first time by alternating a minute of jogging with a minute of walking. My time was 36 minutes flat. Three days later, on March 22, my time was 34:38 by jogging a little more and walking a little less. During that March 22 run, I started thinking about how I could quantify this improvement.

On March 19, my rate of speed was

.

.

On March 22, my rate of speed was

.

.

That’s a change of  over 3 days (accounting for roundoff error in the last decimal place), and so the average rate of change is

over 3 days (accounting for roundoff error in the last decimal place), and so the average rate of change is

.

.

By way of comparison, imagine a keg of beer floating in space. The specifications of beer kegs vary from country to country, but I’ll use the U.S. convention that the mass is 72.8 kg and its height is 23.3 inches = 59.182 cm. Also, for ease of calculation, let’s assume that the keg of beer is a uniformly dense sphere with radius 59.182/2 = 29.591 cm. Under this assumption, the acceleration due to gravity near the surface of the sphere is the same as the acceleration 29.591 cm away from a point-mass of 72.8 kg. Using Newton’s Second Law and the Law of Universal Gravitation, we can solve for the acceleration:

,

,

where  is the gravitational constant,

is the gravitational constant,  is the mass of the beer keg,

is the mass of the beer keg,  is the distance of a particle from the center of the beer keg,

is the distance of a particle from the center of the beer keg,  is the mass of the particle, and

is the mass of the particle, and  is the acceleration of the particle. Solving for

is the acceleration of the particle. Solving for  , we find

, we find

.

.

Since this is only an approximation based on a hypothetical spherical keg of beer, let’s round off and define 1 beerkeg of acceleration to be equal to  .

.

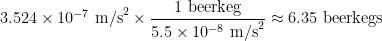

With this new unit, my improvement in speed from March 19 to March 22 can be quantified as

.

.

I love physics: improvements in physical fitness can be measured in kegs of beer.

I chose the beerkeg as the unit of measurement mostly for comedic effect (I’m personally a teetotaler). If the reader desires to present a non-alcoholic version of this calculation to students, I’m sure that coolers of Gatorade would fit the bill quite nicely.

For what it’s worth, at the time of this writing (June 7), my personal record for a 5K is 26:58, and I’m trying hard to get down to 25 minutes. Alas, my current improvements in fitness have definitely witnessed the law of diminishing return and is probably best measured in millibeerkegs.