In this series, I’m looking at a wonderful anecdote from Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard P. Feynman from his book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!. This story concerns a time that he computed  mentally for a few values of

mentally for a few values of  , much to the astonishment of his companions.

, much to the astonishment of his companions.

Part of this story directly ties to calculus.

One day at Princeton I was sitting in the lounge and overheard some mathematicians talking about the series for e^x, which is 1 + x + x^2/2! + x^3/3! Each term you get by multiplying the preceding term by x and dividing by the next number. For example, to get the next term after x^4/4! you multiply that term by x and divide by 5. It’s very simple.

When I was a kid I was excited by series, and had played with this thing. I had computed e using that series, and had seen how quickly the new terms became very small.

As noted, this refers to the Taylor series expansion of  , which is can be used to compute

, which is can be used to compute  to any power. The terms get very small very quickly because of the factorials in the denominator, thus lending itself to the computation of

to any power. The terms get very small very quickly because of the factorials in the denominator, thus lending itself to the computation of  . Indeed, this series is used by modern calculators (with a few tricks to accelerate convergence). In other words, the series from calculus explains how the mysterious “black box” of a graphing calculator actually works.

. Indeed, this series is used by modern calculators (with a few tricks to accelerate convergence). In other words, the series from calculus explains how the mysterious “black box” of a graphing calculator actually works.

Continuing the story…

“Oh yeah?” they said. “Well, then what’s e to the 3.3?” said some joker—I think it was Tukey.

I say, “That’s easy. It’s 27.11.”

Tukey knows it isn’t so easy to compute all that in your head. “Hey! How’d you do that?”

Another guy says, “You know Feynman, he’s just faking it. It’s not really right.”

They go to get a table, and while they’re doing that, I put on a few more figures.: “27.1126,” I say.

They find it in the table. “It’s right! But how’d you do it!”

For now, I’m going to ignore how Feynman did this computation in his head and instead discuss “the table.” The setting for this story was approximately 1940, long before the advent of handheld calculators. I’ll often ask my students, “The Brooklyn Bridge got built. So how did people compute  before calculators were invented?” The answer is by Taylor series, which were used to produce tables of values of

before calculators were invented?” The answer is by Taylor series, which were used to produce tables of values of  . So, if someone wanted to find

. So, if someone wanted to find  , they just had a book on the shelf.

, they just had a book on the shelf.

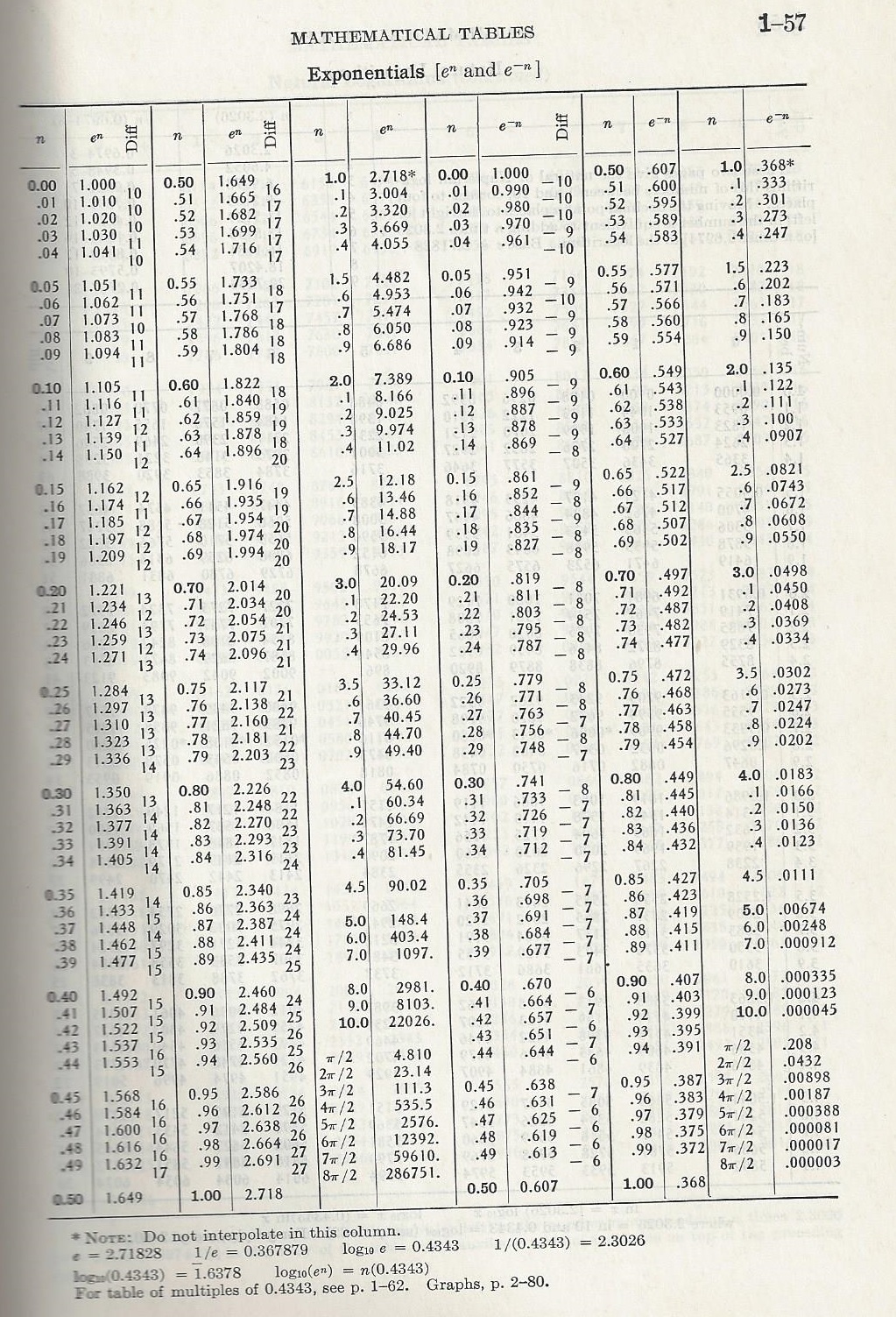

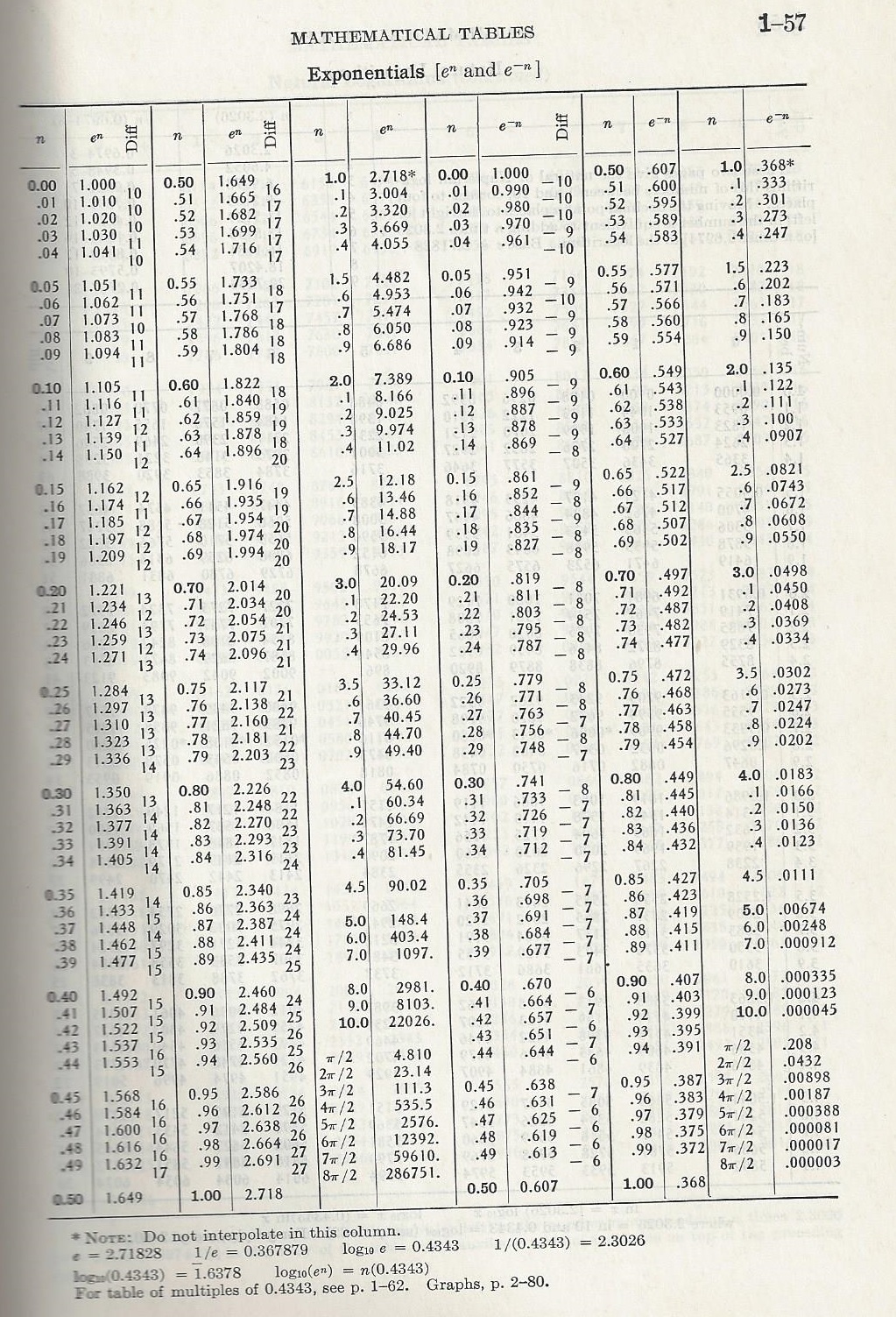

For example, the following page comes from the book Marks’ Mechanical Engineers’ Handbook, 6th edition, which was published in 1958 and which I happen to keep on my bookshelf at home.

Look down the fifth and sixth columns of this table, we see that  . Somebody had computed all of these things (and plenty more) using the Taylor series, and they were compiled into a book and sold to mathematicians, scientists, and engineers.

. Somebody had computed all of these things (and plenty more) using the Taylor series, and they were compiled into a book and sold to mathematicians, scientists, and engineers.

But what if we needed an approximation better more accurate than four significant digits? Back in those days, there were only two options: do the Taylor series yourself, or buy a bigger book with more accurate tables.

.

, the reference Gamma: Exploring Euler’s Constant by Julian Havil kept popping up. Finally, I decided to splurge for the book, expecting a decent popular account of this number. After all, I’m a professional mathematician, and I took a graduate level class in analytic number theory. In short, I don’t expect to learn a whole lot when reading a popular science book other than perhaps some new pedagogical insights.