In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Morgan Mayfield. His topic, from Pre-Algebra: finding points on the coordinate plane.

C2: How has this topic appeared in high culture (art, classical music, theatre, etc.)?

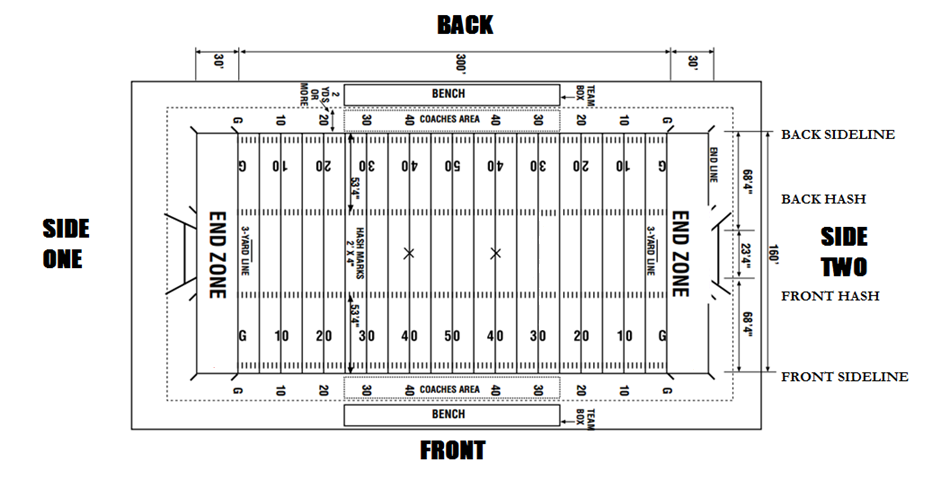

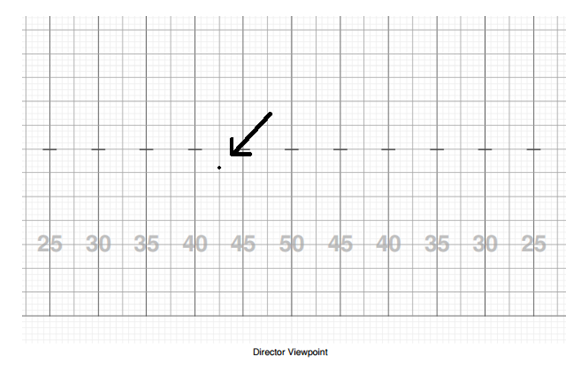

One popular art/sport high school students may take part in is marching band. I did four years of marching band in high school and I loved it. One has to wonder: “how does each performer know where they should be?” I’ve included a link from bandtek.com that describes the coordinate system marching bands use. It isn’t quite the same as the coordinate plane in a math class. When starting marching band, you learn how to take appropriately sized “8 to 5” steps, which simply means 8 equally spaced steps for every 5 yards on a football field. Each member will receive little cards that have “sets” on them. A set is a specific point on the field where the performer must be at a specific time of the show. Usually, performers will take straight paths from set to set in a specific amount of 8-5 steps. Looking at a bird eye’s view of the football field, one can see a rough coordinate plane. Like a coordinate plane has 4 quadrants, a football field has a rough 4 quadrant system where a performer is assigned to stand a specified amount of 8-5 steps from a specified yard line either on side 1 or 2 for their horizontal position and a specified amount of 8-5 steps from the front/back hash for vertical position facing the home sideline. Side 1 refers to the left side of the field from the home side perspective, Side 2 refers to the right side of the field from the home side perspective, and the front/back hash refers to the line of dashes that cut through the middle of the field horizontally from the home side perspective.

An example bandtek.com uses is, “4 outside the side 1 45, 3 in front of the front hash” which would mean the following position:

D1: What interesting things can you say about the people who contributed to the discovery and/or the development of this topic?

René Descartes was a 17th century (1600’s) French mathematician and philosopher. Many people study his work in modern day math and philosophy classes. Some may know him as the man who wrote “cogito, ergo sum” or “I think, therefore I am”. Well, there is a legend about his discovery of the Coordinate Plane. Descartes was often sick as a kid, way before modern medication and technology. He would often have to stay in bed at his boarding school until noon because of his illnesses. This gave him quite a bit of downtime to be observant of his environment. Laying on his bed, he could see a fly crawl around on his ceiling. He thought of ways to describe the location of the fly as it scuttled about the ceiling. Imagine telling a friend where the location of the fly was, “A little to the left of the right wall and a little down from the top wall”. This just isn’t precise enough, nor an easy way to communicate information. However, Descartes realized he could quantify the precise location of the fly from using the distance from a pair of perpendicular walls. Descartes then translated this idea onto a graph where the perpendicular “walls” continued infinitely in both directions and became “axes”. “Flies” then became “points” or “coordinate pairs”. Thus, the coordinate plane was born, and so was a way to describe points in space. Just a little bit of imagination, self-questioning, and observation lead to a fundamental change in Mathematics, a way to tie Algebra and Geometry together.

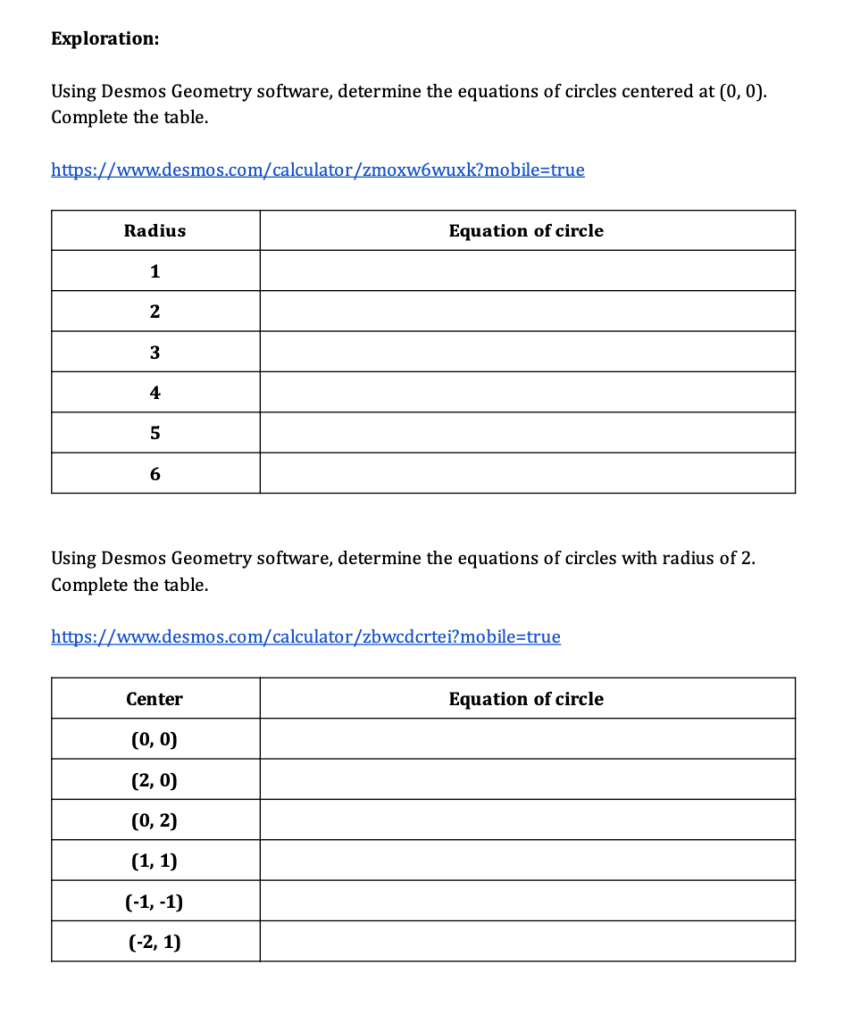

E1: How can technology (YouTube, Khan Academy [khanacademy.org], Vi Hart, Geometers Sketchpad, graphing calculators, etc.) be used to effectively engage students with this topic? Note: It’s not enough to say “such-and-such is a great website”; you need to explain in some detail why it’s a great website.

I believe that https://www.chess.com/vision could be an effective website to engage students on finding points on the coordinate plane in a class that is being introduced to the idea for the first time. Many students won’t know how a chessboard is setup or even know how to play chess. The cool things are that they don’t need to know the fundamentals of chess and that the chessboard is essentially Quadrant I of a coordinate plane (where a1 is in the bottom left corner). The above website tests the player to locate as many squares (points) on a chessboard (coordinate plane) as they can in 30 seconds, given random chess coordinates. There is a way to toggle settings to also test yourself on moves and squares. In a classroom, I would only toggle the setting to list random “black and white squares” where the board is set with a1 at the bottom left corner. Students could start the day with this website as a precursor to formalizing the idea of finding points on a coordinate plane. This website is engaging (with an exclamation point)! The game can be made into a fun little competition amongst students. The time limit and game-y feeling to it encourages active participation. The game takes minimal explanation from the teacher for students to get the hang of it (no chess skills required). The fact that chessboards have one axis in letters and the other axis in numbers aids students in reading the coordinate plane x-axis first, then y-axis like the chess coordinates. I would only have the students run the game for a few rounds, making the activity in total 7 minutes or less.

References:

http://bandtek.com/how-to-read-a-drill-chart/

https://wild.maths.org/ren%C3%A9-descartes-and-fly-ceiling

Have you ever followed a Fly?