Category: Elementary

This Is Why There Are So Many Ties In Swimming

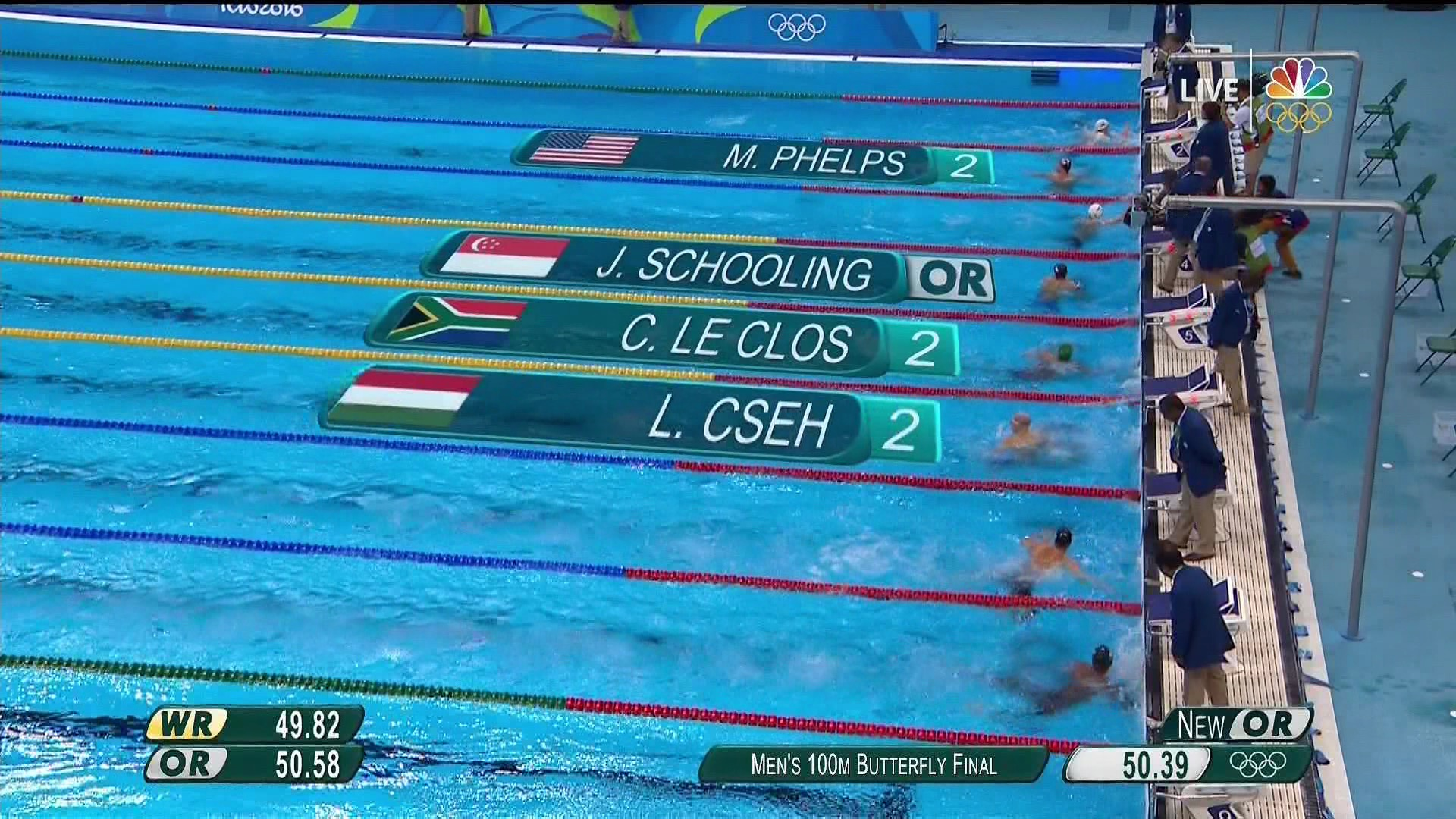

From the excellent article “This Is Why There Are So Many Ties In Swimming“, ties in swimming are allowed by the sport’s governing body because of the inevitability of roundoff error.

In 1972, Sweden’s Gunnar Larsson beat American Tim McKee in the 400m individual medley by 0.002 seconds. That finish led the governing body to eliminate timing by a significant digit. But why?

In a 50 meter Olympic pool, at the current men’s world record 50m pace, a thousandth-of-a-second constitutes 2.39 millimeters of travel. FINA pool dimension regulations allow a tolerance of 3 centimeters in each lane, more than ten times that amount. Could you time swimmers to a thousandth-of-a-second? Sure, but you couldn’t guarantee the winning swimmer didn’t have a thousandth-of-a-second-shorter course to swim. (Attempting to construct a concrete pool to any tighter a tolerance is nearly impossible; the effective length of a pool can change depending on the ambient temperature, the water temperature, and even whether or not there are people in the pool itself.)

Another Poorly Written Word Problem: Index

I’m doing something that I should have done a long time ago: collecting a series of posts into one single post. The following links comprised my series poorly written word problem, taken directly from textbooks and other materials from textbook publishers.

Part 1: Addition and estimation.

Part 2: Estimation and rounding.

Part 3: Probability.

Part 4: Subtraction and estimation.

Part 5: Algebra and inequality.

Part 6: Domain and range of a function.

Part 7: Algebra and inequality.

Part 8: Algebra and inequality.

Part 9: Geometric series.

Abbott and Costello and subtraction

For more on Abbott and Costello and mathematics, here’s the classic routine “Two Tens for a Five.” (On my first job as a teenager, my boss successfully pulled this joke on me using two dimes and a nickel.)

Calculus and Abbott and Costello

Although for all

, it’s also true that

.

That’s the subtle mathematical premise behind this classic comedy routine from Abbott and Costello. (This routine was the basis of a recent article in The College Mathematics Journal.)

Combinatorics and Jason’s Deli (Part 3)

Jason’s Deli is one of my family’s favorite places for an inexpensive meal. Recently, I saw the following placard at our table advertising their salad bar:

The small print says “Math performed by actual rocket scientist”; let’s see how the rocket scientist actually did this calculation.

In yesterday’s post, I showed that the rocket scientist correctly calculated

.

To impress upon customers just how large this number is, the advertisers imagine eating a different salad every day until all 1,906,884 possibilities had been exhausted. Since there are 365 days in a year, apparently the rocket scientist divided:

Unfortunately, there’s a small problem: the rocket scientist forgot about leap years! Ignoring for now the adjustments of the Gregorian calendar (years divisible by 1000 but not 4000 aren’t leap years — so that 2000 was a leap year but 2100 won’t be), we should divide not by 365 but by 365.25:

Over a span of 5,220 years, there might be 3 or 4 extra leap days in the above calculation (depending on when someone starts eating the salads), not enough to throw off the above calculation by too much. So the correct answer, rounded to the nearest integer, really should have been 5,221 years.

All this to say, ignoring leap years caused the rocket scientist to give an answer that was off by 3.

Abbott and Costello and division

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 7b)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprising depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received after a really big hailstorm:

How big would a 1000-pound hailstone be?

The guesses from the students ranged from the size of a small car to the size of a large pick-up truck. Here’s how I gave a reasonably accurate answer using only mental arithmetic. This kind of describes the way that I try to size up things when only an approximation (and not an exact answer) is necessary.

First, I had some real-world experience that quickly told me the answer was going to be deceptively small. When I was young — maybe 10 or 12 years old — I was getting ready for a picnic, and I was assigned cut a block of ice — maybe a cubic foot of ice, if memory serves — into smaller chunks. (The party organizer bought a block of ice instead of a bag of ice to economize.) I remembered how incredibly heavy that block of ice was even though it wasn’t much larger than a basketball… several of us kids had a lot of trouble lifting the block of ice as we prepared to chop it into pieces. So, for the sake of argument, if that cubic foot of ice weighed about 100 pounds, then 8 cubic feet would weigh 800 pounds. So, based on that chance encounter with a block of ice when I was a kid, my guess would have been that the hailstone would measure 2 feet across.

Back to the problem at hand.

First, I converted to metric. I knew that there are about 2.2 pounds in a kilogram, and so I knew that the block would weigh something like 400 or 450 kilograms. I knew that I would be making plenty of crude approximations, so I just went with 400 kilograms and didn’t worry too much about immediately calculating .

Next, I knew that metric units were originally defined so that a cubic centimeter of water weighs a gram, so that a 10 cm-by-10 cm-by 10 cm cube of water weighs one kilogram. Ice (hail) is slightly less dense than water (after all, ice floats in water), but for crude approximation purposes, I ignored this.

So, if a cube of ice with a side length of 1 decimeter (10 cm) weighs 1 kilogram, then a cube of ice with a side length of decimeters would weigh about 400 kilograms.

How big is ? Well, I have memorized that

and

, so it’s between 7 and 8 someplace… say 7.5. So the answer would be a cube of side length 7.5 decimeters. Also, I have memorized that 1 decimeter (10 cm) is approximately 4 inches, so the cube would have side length

inches.

Finally, hailstones are more spherical in shape than cubic, and a sphere of diameter has less volume than a cube of side length

. So the answer should be a bit larger than 30 inches, so I just rounded up to a nice even number: 36 inches (one yard).

This calculation took me about a minute to do in my head and another half-minute to re-do to make sure I didn’t botch the arithmetic. So I held my hands about a yard apart (perhaps the crudest part of this calculation), pretending to hold a ball of diameter a yard across, and announced, “The hailstone would be about this big.”

Of course, a more thoughtful analysis produces the actual answer. The density of ice at the freezing point is 0.9167 grams per cubic centimeter, and 1 pound converts to 0.453592 kilograms. So:

Of course, a more thoughtful analysis produces the actual answer. The density of ice at the freezing point is 0.9167 grams per cubic centimeter, and 1 pound converts to 0.453592 kilograms. So:

Therefore, the sphere would have a diameter of twice that, or 38.6 inches.

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary school students (Part 7a)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprising depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received after a really big hailstorm:

How big would a 1000-pound hailstone be?

My head hurts thinking about hail that large. After about a minute of thinking, without using a calculator or even a pencil, I gave my answer: about a yard across.

I’ll reveal how I got this answer — which turns out to be a lot close than I had any right to expect — in tomorrow’s post. In the meantime, I’ll leave a thought bubble if you’d like to think about it on your own without using a calculator.

Lessons from teaching gifted elementary students (Part 6b)

Every so often, I’ll informally teach a class of gifted elementary-school students. I greatly enjoy interacting with them, and I especially enjoy the questions they pose. Often these children pose questions that no one else will think about, and answering these questions requires a surprising depth of mathematical knowledge.

Here’s a question I once received:

255/256 to what power is equal to 1/2? And please don’t use a calculator.

Here’s how I answered this question without using a calculator… in fact, I answered it without writing anything down at all. I thought of the question as

.

I was fortunate that my class chose 1/2, as I had memorized (from reading and re-reading Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! when I was young) that . Therefore, we have

.

Next, I used the Taylor series expansion

to reduce this to

,

or

.

For my students’ problem, I had , and so

.

So all I had left was the small matter of multiplying these two numbers. I thought of this as

.

Multiplying and

in my head took a minute or two:

.

Therefore, and

. Therefore, I had the answer of

.

So, after a couple minutes’ thought, I gave the answer of 177. I knew this would be close, but I had no idea it would be so close to the right answer, as