In this series, I’m discussing how ideas from calculus and precalculus (with a touch of differential equations) can predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit and thus confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The origins of this series came from a class project that I assigned to my Differential Equations students maybe 20 years ago.

We previously showed that if the motion of a planet around the Sun is expressed in polar coordinates , with the Sun at the origin, then under Newtonian mechanics (i.e., without general relativity) the motion of the planet follows the differential equation

,

where and

is a certain constant. We will also impose the initial condition that the planet is at perihelion (i.e., is closest to the sun), at a distance of

, when

. This means that

obtains its maximum value of

when

. This leads to the two initial conditions

;

the second equation arises since has a local extremum at

.

We now take the perspective of a student who is taking a first-semester course in differential equations. There are two standard techniques for solving a second-order non-homogeneous differential equations with constant coefficients. One of these is the method of undetermined coefficients. First, we solve the associated homogeneous differential equation

.

The characteristic equation of this differential equation is , which clearly has the two imaginary roots

. Therefore, the solution of the associated homogeneous equation is

.

(As an aside, this is one answer to the common question, “What are complex numbers good for?” The answer is naturally above the heads of Algebra II students when they first encounter the mysterious number , but complex numbers provide a way of solving the differential equations that model multiple problems in statics and dynamics.)

Next, we find a particular solution to the original differential equation. Since the right-hand side is a constant and is not a solution of the characteristic equation, this leads to trying something of the form

as a solution, where

is a soon-to-be-determined constant. (Guessing this form of

is a standard technique from differential equations; later in this series, I’ll give some justification for this guess.)

Clearly, and

. Substituting, we find

Therefore, is a particular solution of the nonhomogeneous differential equation.

Next, the general solution of the nonhomogeneous differential equation is found by adding the general solution to the associated homogeneous differential equation and the particular solution:

.

Finally, to determine and

, we use the initial conditions

and

. From the first initial condition,

From the second initial condition,

.

From these two constants, we obtain

,

where .

Finally, since , we see that the planet’s orbit satisfies

,

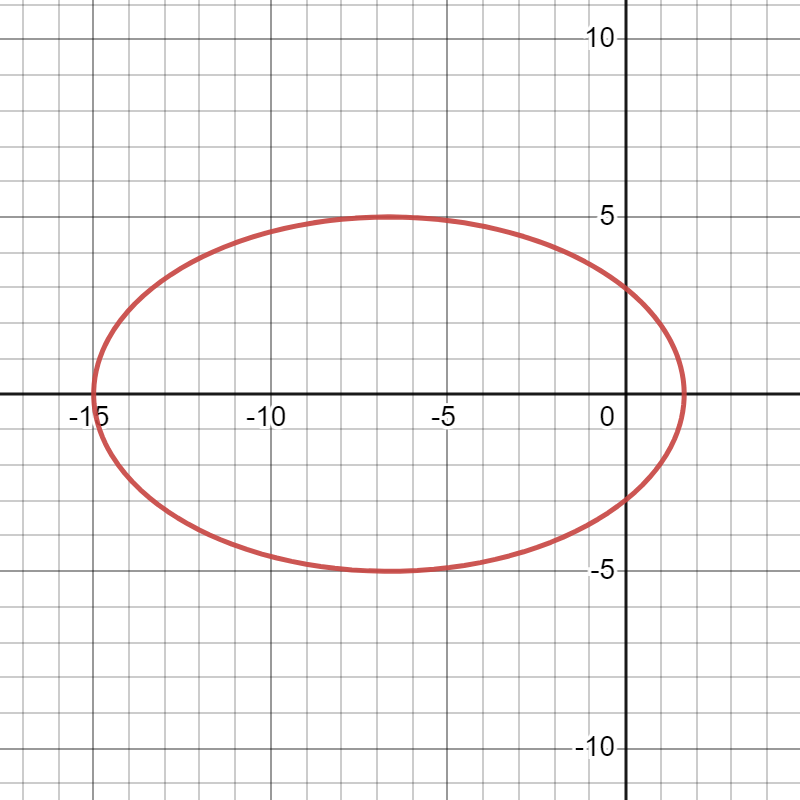

so that, as shown earlier in this series, the orbit is an ellipse with eccentricity .

The reader will notice that this solution is pretty much a carbon-copy of the previous post. The difference is that calculus students wouldn’t necessarily be able to independently generate the solutions of the associated homogeneous differential equation and a particular solution of the nonhomogeneous differential equation, and so the line of questioning is designed to steer students toward the answer.