In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission again comes from my former student Nada Al-Ghussain. Her topic, from Algebra: graphs of linear equations.

How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

Positive slope, negative slope, no slope, and undefined, are four lines that cross over the coordinate plane. Boring. So how can I engage my students during the topic of graphs of linear equations, when all they can think of is the four images of slope? Simple, I assign a project that brings out the Individuality and creativity of each student. Something to wake up their minds!

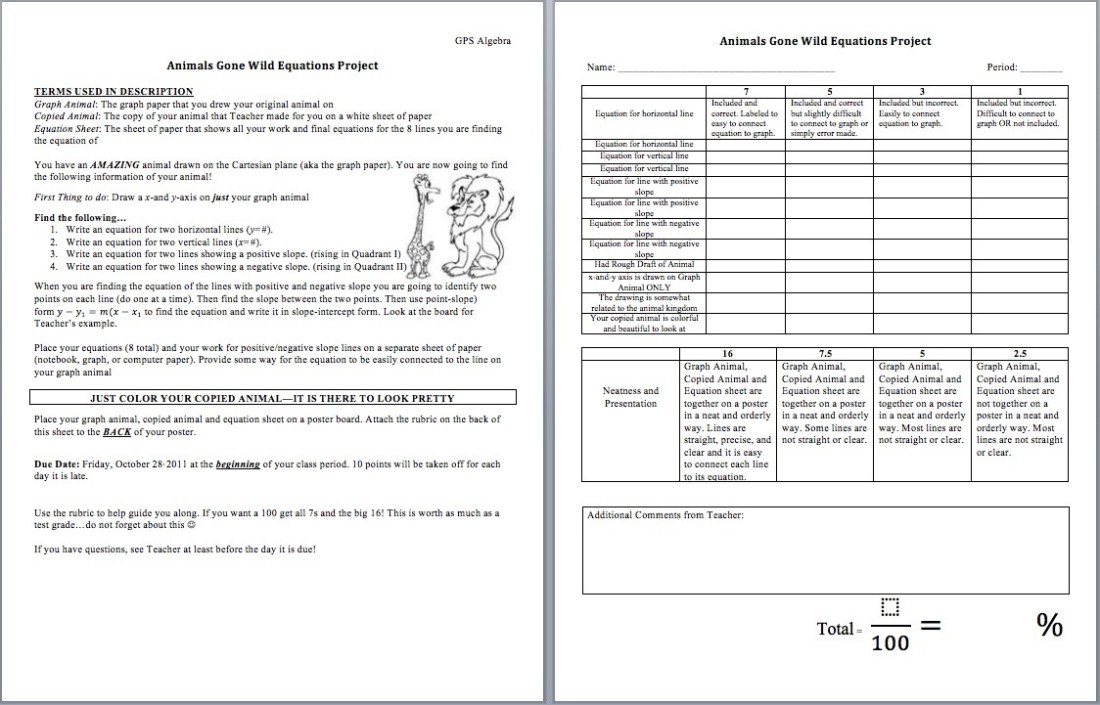

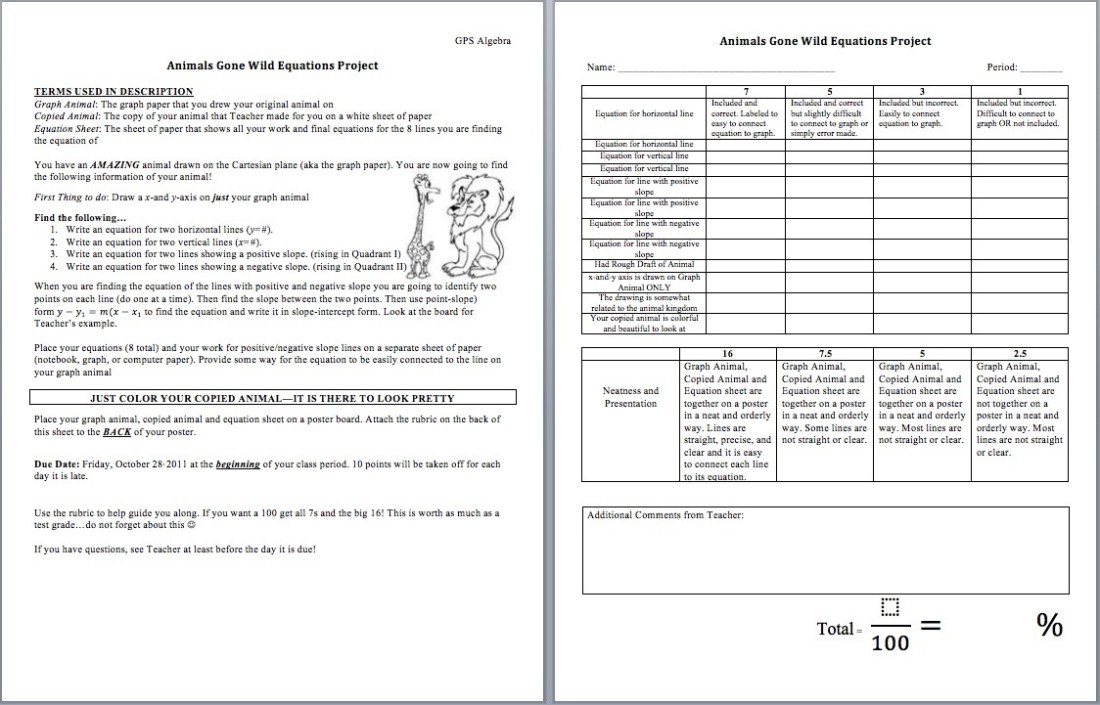

An individualized image-graphing project. I would give each student a large coordinate plane, where they will graph their picture using straight lines only. I would ask them to use only points at intersections, but this can change to half points if needed. Then each student will receive an Equation sheet where they will find and write 2 equations for each different type of slope. So a student will have equations for two horizontal lines, vertical lines, positive slope, and negative slope. The best part is the project can be tailored to each class weakness or strength. I can also ask them to write the slop-intercept form, point slope form, or to even compare slopes that are parallel or perpendicular. When they are done, students would have practiced graphing and writing linear equations many times using their drawn images. Some students would be able to recognize slopes easier when they recall this project and their specific work on it.

Example of a project template:

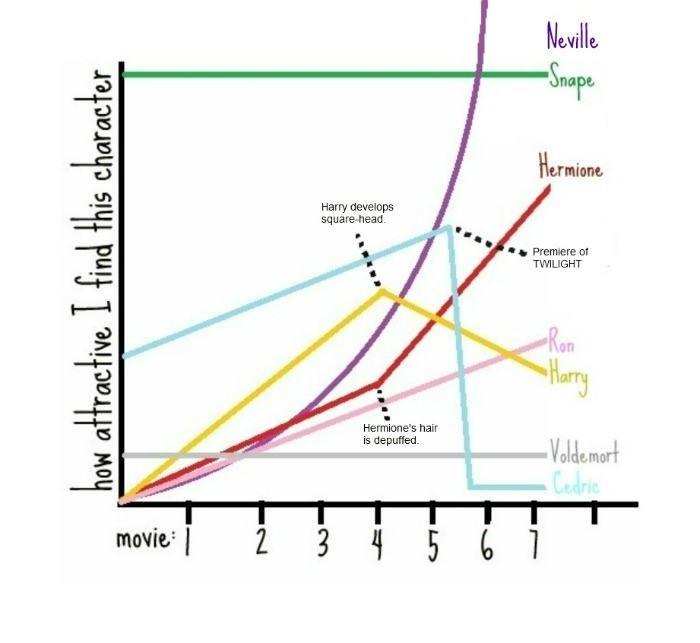

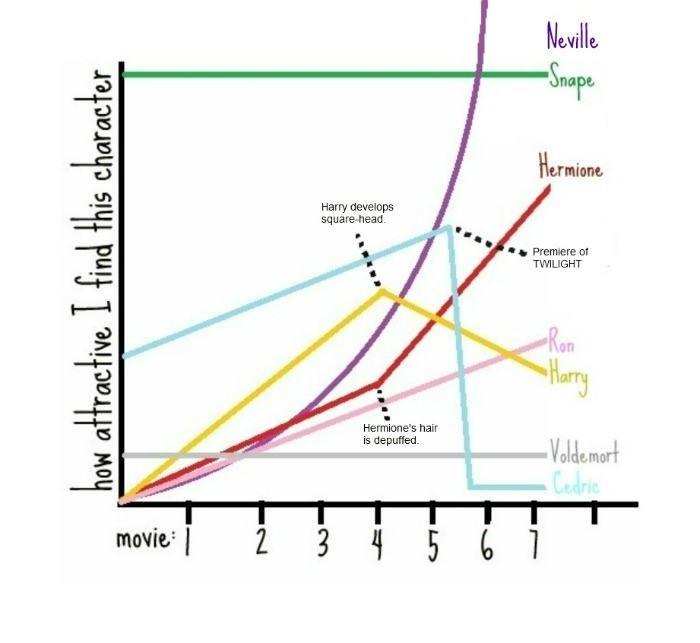

Examples of student work:

How has this topic appeared in the news?

Millions of people tune in to watch the news daily. Information is poured into our ears and images through our eyes. We cannot absorb it all, so the news makes it easy for us to understand and uses graphs of linear equations. Plus, the Whoa! Factor of the slopping lines is really the attention grabber. News comes in many forms either through, TV, Internet, or newspaper. Students can learn to quickly understand the meaning of graphs with the different slopes the few seconds they are exposed to them.

On television, FOX news shows a positive slope of increasing number of job losses through a few years. (Beware for misrepresented data!)

A journal article contains the cost of college increase between public and private colleges showing the negative slope of private costs decreasing.

Most importantly line graphs can help muggles, half bloods, witches, and wizards to better understand the rise and decline of attractive characters through the Harry Potter series.

How can this topic be used in your students’ future courses in mathematics or science?

Students are introduced to simple graphs of linear equations where they should be able to name and find the equation of the slope. In a student’s future course with computers or tablets, I would use the Desmos graphing calculator online. This tool gives the students the ability to work backwards. I would ask a class to make certain lines, and they will have to come up with the equation with only their knowledge from previous class. It would really help the students understand the reason behind a negative slope and positive slope plus the difference between zero slope and undefined. After checking their previous knowledge, students can make visual representations of graphing linear inequalities and apply them to real-world problems.

References:

http://www.hoppeninjamath.com/teacherblog/?p=217

http://walkinginmathland.weebly.com/teaching-math-blog/animal-project-graphing-linear-lines-and-stating-equations

http://mediamatters.org/research/2012/10/01/a-history-of-dishonest-fox-charts/190225

http://money.cnn.com/2010/10/28/pf/college/college_tuition/

http://dailyfig.figment.com/2011/07/13/harry-potter-in-charts/

https://www.desmos.com/calculator

.

.