In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission again comes from my former student Loc Nguyen. His topic, from Algebra: fitting data to a quadratic function.

A1. What interesting (i.e., uncontrived) word problems using this topic can your students do now?

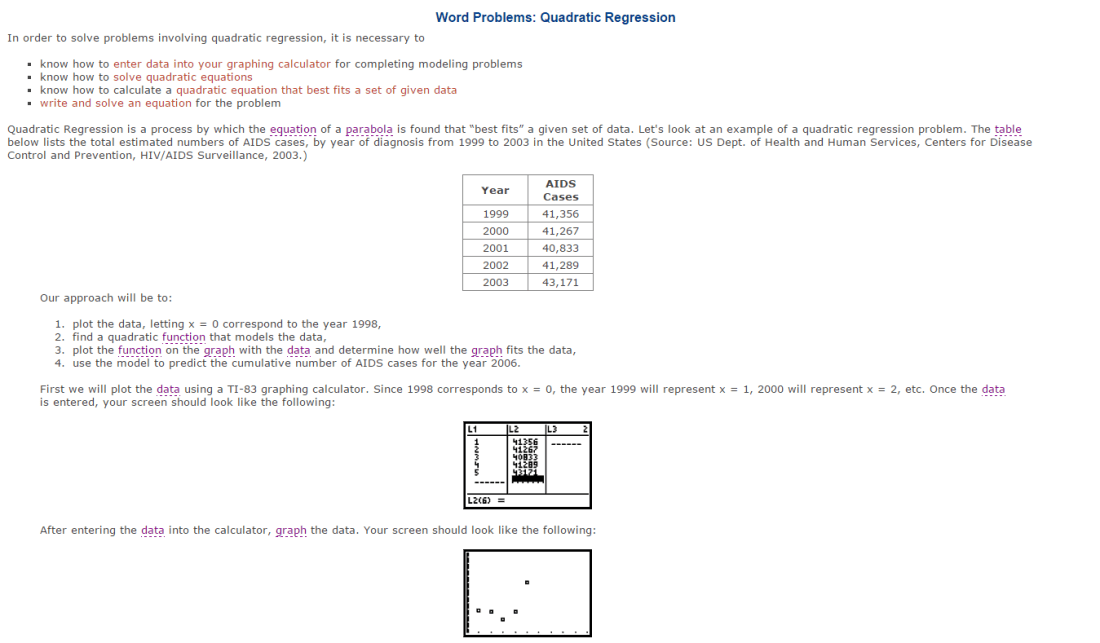

To engage students on this topic, I will provide them the word problems in the real life so they can see the usefulness of quadratic regression in predictive purposes. The question to the problem is about the estimated numbers of AIDS cases that can be diagnosed in 2006. The data only show from 1999 to 2003. This will be students’ job to figure out the prediction. I will provide the instructions for this task and I will also walk them through the process of finding the best curve that fit the given data. The best fit to the curve will give us the estimation. Here is how the instruction looks like:

In the end, students will be able to acquire the parabola curve which fit the given data. By letting students work through the real life problems, they will be able to understand why mathematics is important and see how this concept is useful in their lives.

B2. How does this topic extend what your students should have learned in previous courses?

Before getting into this topic, the students should have eventually been familiar with the word “quadratic” such as quadratic function, quadratic equation. Students should have been taught when the curve concaves up or down. In the previous course, students would be given the quadratic functions and they would be asked to find the maxima, minima, or intercepts. Or they would be asked to solve the quadratic equation and find the roots. The universal properties of quadratic function never change. When students encountered the concept of quadratic regression, they would not be so overwhelmed with the topic. There is no new rule or properties. The process is just backward. The Instead of having the given function, in this case, students will have to find the function based on the given data so that the curve would fit the data. Their prior knowledge is really essential for this topic, and this would help them to understand the concept of quadratic regression easier.

C1. How has this topic appeared in pop culture (movies, TV, current music, video games, etc.)?

At the beginning of the class, I would like to show students the short video of football incident.

This incident was really interesting. The Titans punt went so high so that it hit the scoreboard in Cowboys stadium. Surprisingly, this was Cowboy’s new stadium. There were many questions about what was going on when the architecture built this stadium. It was supposed to be great. This incident revealed the errors in predicting the height of the scoreboard. The data they collected in past year may have been incorrect. I want to incorporate this incident into the concept of quadratic regression. I will pose several questions such as:

Was Titan football punter really that powerful? What was really wrong in this situation?

When the architectures built this stadium, did they ever think that the ball would reach the ceiling?

How come did the architectures fail to measure the height of the ceiling? Did they just assume the height of the stadium tall enough?

What was the path of the ball?

Students will eagerly respond to these questions, and I will slowly bring in the important of quadratic regression. I will then explain how quadratic regression helps us to predict the height based on collected data from past years.

References:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V4N3LEi5a1Q

http://www.algebralab.org/Word/Word.aspx?file=Algebra_QuadraticRegression.xml