In this series, I’m discussing how ideas from calculus and precalculus (with a touch of differential equations) can predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit and thus confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The origins of this series came from a class project that I assigned to my Differential Equations students maybe 20 years ago.

In this series, we found an approximate solution to the governing initial-value problem

,

where ,

,

,

is the gravitational constant of the universe,

is the mass of the planet,

is the mass of the Sun,

is the constant angular momentum of the planet,

is the eccentricity of the orbit, and

is the speed of light.

We used the following steps to find an approximate solution.

Step 0. Ignore the general-relativity contribution and solve the simpler initial-value problem

,

which is a zeroth-order approximation to the real initial-value problem. We found that the solution of this differential equation is

,

which is the equation of an ellipse in polar coordinates.

Step 1. Solve the initial-value problem

,

which partially incorporates the term due to general relativity. This is a first-order approximation to the real differential equation. After much effort, we found that the solution of this initial-value problem is

.

For large values of , this is accurately approximated as:

,

which can be further approximated as

.

From this expression, the precession in a planet’s orbit due to general relativity can be calculated.

Roughly 20 years ago, I presented this application of differential equations at the annual meeting of the Texas Section of the Mathematical Association of America. After the talk, a member of the audience asked what would happen if we did this procedure yet again to find a second-order approximation. In other words, I was asked to consider…

Step 2. Solve the initial-value problem

.

It stands to reason that the answer should be an even more accurate approximation to the true solution .

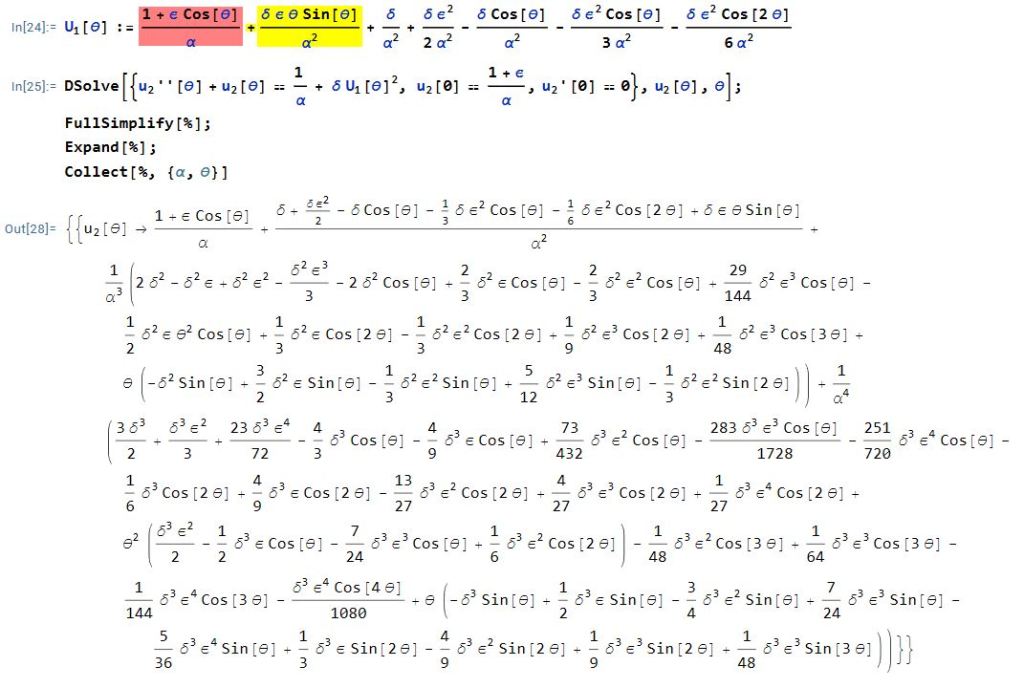

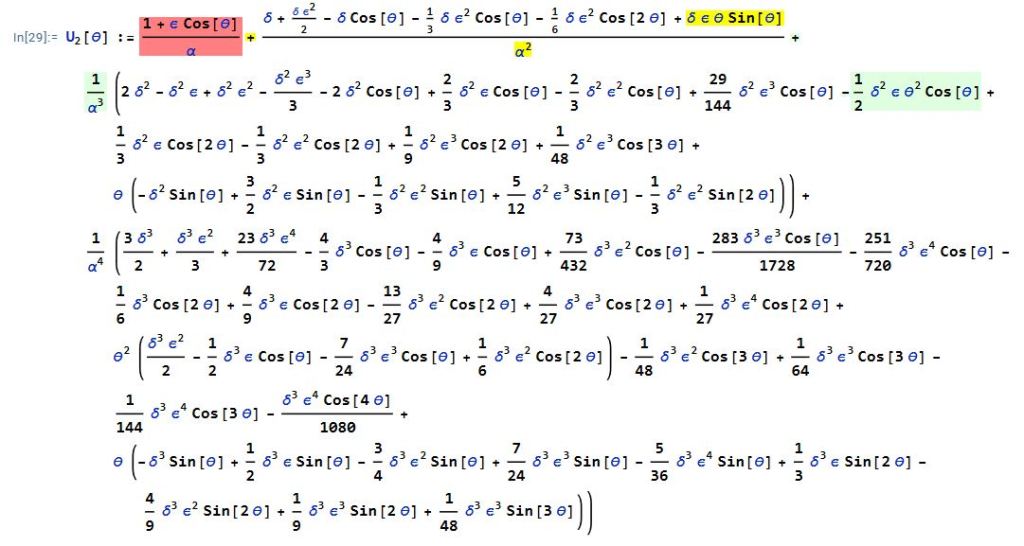

I didn’t have an immediate answer for this question, but I can answer it now. Letting Mathematica do the work, here’s the answer:

Yes, it’s a mess. The term in red is , while the term in yellow is the next largest term in

. Both of these appear in the answer to

.

The term in green is the next largest term in , with the highest power of

in the numerator and the highest power of

in the denominator. In other words,

.

How does this compare to our previous approximation of

?

Well, to a second-order Taylor approximation, it’s the same! Let

.

Expanding about and treated

as a constant, we find

.

Substituting yields the above approximation for

.

Said another way, proceeding to a second-order approximation merely provides additional confirmation for the precession of a planet’s orbit.

Just for the fun of it, I also used Mathematica to find the solution of Step 3:

Step 2. Solve the initial-value problem

.

I won’t copy-and-paste the solution from Mathematica; unsurpisingly, it’s really long. I will say that, unsurprisingly, the leading terms are

.

I said “unsurprisingly” because this matches the third-order Taylor polynomial of our precession expression. I don’t have time to attempt it, but surely there’s a theorem to be proven here based on this computational evidence.

One thought on “Confirming Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity With Calculus, Part 8: Second- and Third-Order Approximations”