In this series, I’m discussing how ideas from calculus and precalculus (with a touch of differential equations) can predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit and thus confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The origins of this series came from a class project that I assigned to my Differential Equations students maybe 20 years ago.

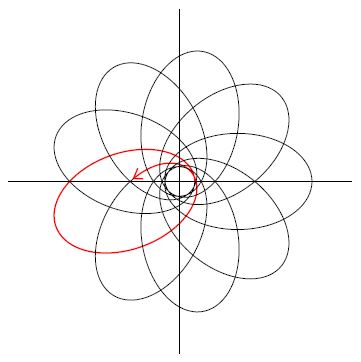

The figure below shows the (greatly exaggerated) effect of precession on a planet’s otherwise elliptical orbit. In the figure, each perihelion is precessed by an angle of . After nine orbits, the planet returns to its original position. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that each orbit of the planet depicted in the figure is four months, or one third of Earth’s year. Then the amount of precession would be

per four months, or

per year, or

per century.

As I said, the figure above is greatly exaggerated. As we’ll see by the end of this series, Einstein’s general relativity predicts that, on top of the gravitational influences of the other planets, the orbit of Mercury should precess by 43″ of arc per century. That’s a really small angle, since 1 is equal to 60′ (minutes) of arc and each 1′ is equal to 60″ (seconds) of arc, that means 1″ of arc is the same as

, so that 43″ of arc per century is about

per century. That’s about a million times smaller than the precession of the fictitious planet in the above figure.

How small is , really?

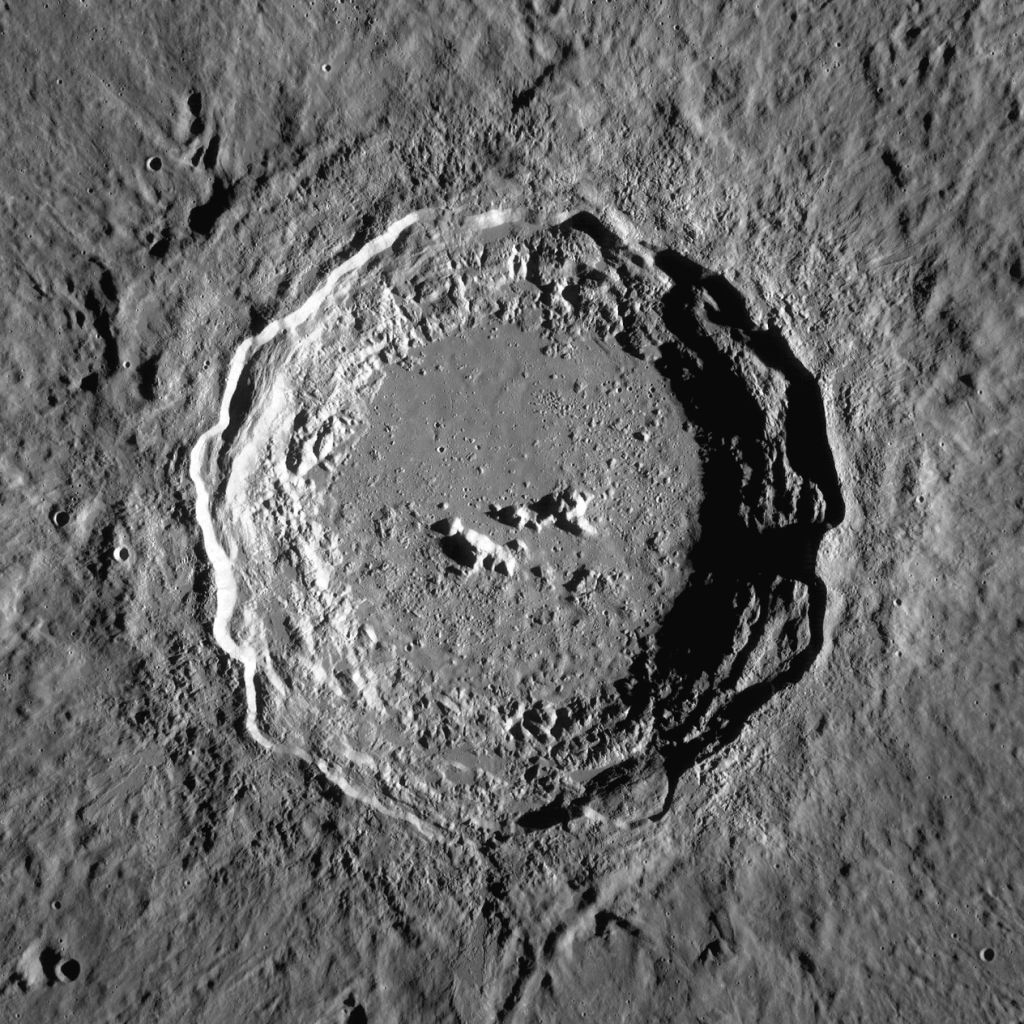

Courtesy of Wikipedia, the pictures below are the Copernicus crater on the Moon as well as an indicator of its location on the Moon. It is visible with binoculars.

The diameter of the crater is 93 km. Since the Moon is 384,400 km from Earth, that means the angle subtended by the crater, as viewed from the Earth, is about

.

So how much is 43″ of arc per century? That’s about the speed as, hypothetically, pointing at the left edge of this lunar crater (which cannot be seen by the naked eye) and then slowly moving your figure so that, about 115 years later, your finger is pointing at the right edge of the crater.

Said another way, the diameter of the Moon is about 3475 km, so that the angle subtended by the Moon, as viewed from the Earth, is about

.

So, at the rate of per century, it would take

centuries, or about 43,000 years, to trace the angle subtended by the moon.

Needless to say, 43” of arc per century is really, really slow.

Nevertheless, and remarkably, this itty, bitty precession was observable by careful 19th century astronomers with the telescopes that were available then. At the time, this precession was the great unsolved mystery of Newtonian physics that was only answered after two generations later with the discovery of general relativity.

One thought on “Confirming Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity With Calculus, Part 1b: Precession of Mercury”