Students at all levels — elementary, middle, secondary, and college — tend to think that either (1) all the problems in mathematics have already been solved, or else (2) some unsolved problems remain but only an expert can understand even the statement of the problem.

Here’s the statement of the problem.

That’s it. From Wikipedia:

For instance, starting with 6, one gets the sequence 6, 3, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

Starting with 11, for example, takes longer to reach 1: 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

The sequence for 27 takes 111 steps, climbing to 9232 before descending to 1: 27, 82, 41, 124, 62, 31, 94, 47, 142, 71, 214, 107, 322, 161, 484, 242, 121, 364, 182, 91, 274, 137, 412, 206, 103, 310, 155, 466, 233, 700, 350, 175, 526, 263, 790, 395, 1186, 593, 1780, 890, 445, 1336, 668, 334, 167, 502, 251, 754, 377, 1132, 566, 283, 850, 425, 1276, 638, 319, 958, 479, 1438, 719, 2158, 1079, 3238, 1619, 4858, 2429, 7288, 3644, 1822, 911, 2734, 1367, 4102, 2051, 6154, 3077, 9232, 4616, 2308, 1154, 577, 1732, 866, 433, 1300, 650, 325, 976, 488, 244, 122, 61, 184, 92, 46, 23, 70, 35, 106, 53, 160, 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

The longest progression for any initial starting number less than 100 million is 63,728,127, which has 949 steps. For starting numbers less than 1 billion it is 670,617,279, with 986 steps, and for numbers less than 10 billion it is 9,780,657,630, with 1132 steps.

Like I said, this is an easily stated problem that most fourth graders could understand. And no one knows the answer. Every number that’s been tried by computer has produced a sequence that eventually reaches  . But that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a bigger number out there that doesn’t reach

. But that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a bigger number out there that doesn’t reach  .

.

I’ll refer to the above Wikipedia page (and references therein) for further reading about the Collatz conjecture. Pedagogically, I suggest that casually mentioning this unsolved problem in class might inspire students to play with mathematics on their own, rather than think that all of mathematics has already been solved by somebody.

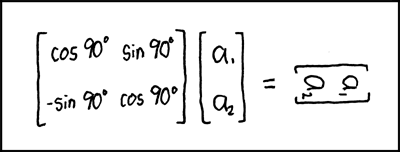

… the matrix is an example of a rotation matrix. This concept appears quite frequently in linear algebra (not to mention video games and computer graphics). In the secondary mathematics curriculum, this device is often used to determine how to graph conic sections of the form

,

. I’ll refer to the MathWorld and Wikipedia pages for more information.