In this series of posts, I explore properties of complex numbers that explain some surprising answers to exponential and logarithmic problems using a calculator (see video at the bottom of this post). These posts form the basis for a sequence of lectures given to my future secondary teachers.

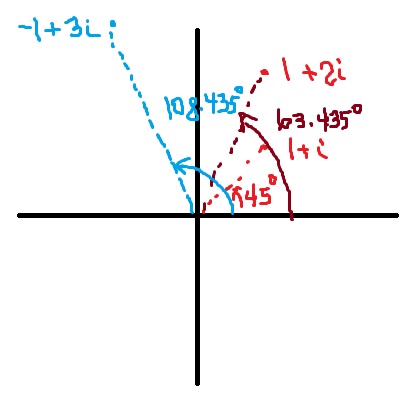

To begin, we recall that the trigonometric form of a complex number is

where and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant. As noted before, this is analogous to converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

There’s a shorthand notation for the right-hand side () that I’ll justify later in this series.

In the previous three posts, we discussed De Moivre’s Theorem:

Theorem. If is an integer, then

.

Let’s now use this theorem to solve an algebraic equation.

Find all

so that

.

When I present this to my students, their kneejerk reaction is always to answer “.” To which I politely point out, “This is a cubic equation. So how many roots does it have?” Of course, they answer “Three.” To which I respond, “OK, so how do we find the other two roots?”

With enough patience, a student will usually volunteer that has a known root of

, and so the remaining roots can be found using synthetic division by dividing

into

, yielding

So the other two roots can be found using the quadratic formula:

So there are indeed three roots. Though I usually won’t take class time to do it, I encourage my students to cube these two answers to confirm that they indeed get .

As an aside, before moving on to the use of De Moivre’s Theorem, I usually point out to my students that there is a formula for factoring the sum of two cubes:

And there’s a formula for the difference of two cubes:

My experience is that even math majors are not familiar with these two formulas. They know the difference of two squares formula, but they’re either not proficient with these two formulas or else they’ve never seen them before. These can be generalized for any odd positive exponent and any positive exponent, respectively.

In tomorrow’s post, I’ll describe how these three roots can be found by using De Moivre’s Theorem.

For completeness, here’s the movie that I use to engage my students when I begin this sequence of lectures.