In the course of evaluating the antiderivative

,

,

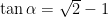

I have stumbled across a very curious trigonometric identity:

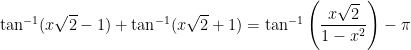

if

if  ,

,

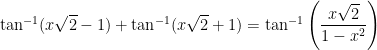

if

if  ,

,

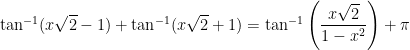

if

if  ,

,

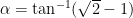

where  and

and  are the unique values so that

are the unique values so that

,

,

.

.

I will now show that  and

and  . Indeed, it’s apparent that these have to be the two transition points because these are the points where

. Indeed, it’s apparent that these have to be the two transition points because these are the points where  is undefined. However, it would be more convincing to show this directly.

is undefined. However, it would be more convincing to show this directly.

To show that  , I need to show that

, I need to show that

.

.

I could do this with a calculator…

…but that would be cheating.

…but that would be cheating.

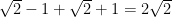

Instead, let  and

and  , so that

, so that

,

,

.

.

Indeed, by SOHCAHTOA, the angles  and

and  can be represented in the figure below:

can be represented in the figure below:

The two small right triangles make one large triangle, and I will show that the large triangle is also a right triangle. To do this, let’s find the lengths of the three sides of the large triangle. The length of the longest side is clearly

The two small right triangles make one large triangle, and I will show that the large triangle is also a right triangle. To do this, let’s find the lengths of the three sides of the large triangle. The length of the longest side is clearly  . I will use the Pythagorean theorem to find the lengths of the other two sides. For the small right triangle containing

. I will use the Pythagorean theorem to find the lengths of the other two sides. For the small right triangle containing  , the missing side is

, the missing side is

Next, for the small right triangle containing  , the missing side is

, the missing side is

So let me redraw the figure, eliminating the altitude from the previous figure:

Notice that the condition of the Pythagorean theorem is satisfied, since

,

,

or

.

.

Therefore, by the converse of the Pythagorean theorem, the above figure must be a right triangle (albeit a right triangle with sides of unusual length), and so  . In other words,

. In other words,  , as required.

, as required.

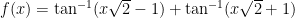

To show that  , I will show that the function

, I will show that the function  is an odd function using the fact that

is an odd function using the fact that  is also an odd function:

is also an odd function:

![= \tan^{-1} ( -[x\sqrt{2} + 1] ) + \tan^{-1}( -[x \sqrt{2} - 1])](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%3D+%5Ctan%5E%7B-1%7D+%28+-%5Bx%5Csqrt%7B2%7D+%2B+1%5D+%29+%2B+%5Ctan%5E%7B-1%7D%28+-%5Bx+%5Csqrt%7B2%7D+-+1%5D%29&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

![= - \left[ \tan^{-1} ( x\sqrt{2} + 1 ) + \tan^{-1}( x \sqrt{2} - 1) \right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%3D+-+%5Cleft%5B+%5Ctan%5E%7B-1%7D+%28+x%5Csqrt%7B2%7D+%2B+1+%29+%2B+%5Ctan%5E%7B-1%7D%28+x+%5Csqrt%7B2%7D+-+1%29+%5Cright%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

.

.

Therefore,  , and so

, and so  .

.

,

,

.