Here is one school’s results from a (relatively) recent track and field meet. Never mind the name of the school or the names of the athletes representing the school; this is a math blog and not a sports blog, even though I’m an avid sports fan. Furthermore, I have nothing but respect for young people who are both serious students and serious athletes. While I have no illusions about the global popularity of this blog, and while the information from the meet are in the public domain, I also have no desire to inadvertently subject these student-athletes to online abuse.

With that preamble, here are the school’s results:

The unusual score for jumps caught my attention. Clearly a score of was intended, but this isn’t displayed. (This is also a lesson about using unnecessary precision… unlike the total points field showing 152.33.) Before this unusual decimal expansion, however, I should generally describe how teams are scored at a track and field meet… or at least the high school and college meets that I’ve attended in the United States.

Each meet has multiple events, often categorized as sprints, hurdles, distance races, throwing events, jumping events, relay races, and multi-sport events (like the decathlon). At each event, first place gets 10 points, second place gets 8 points, third place gets 6 points, fourth place gets 5 points, fifth place gets 4 points, sixth place gets 3 points, seventh place gets 2 points, and eighth place gets 1 point.

Let’s explain the last two lines first. At this meet, athletes from this team finished second, sixth, and seventh in the one multi-sport event, earning points for the school. A relay team finished third in the 4×100 meter relay, earning another 6 points for the school.

The third-to-last line — jumps — requires some explanation. No athlete from the school finished in top eight in the long jump or the triple jump (0 points). One athlete won the high jump (10 points). And one athletic finished in a three-way tie for second place in the pole vault. In the case of such a tie, the points for second, third, and fourth place are averaged and given to all three competitors, for points. In total, the school earned

points from the jumping events.

In jumping events, it is possible (but rare) for athletes to tie. The table above shows the results of the competition for the top eight finishers. The lingo: P means the competitor passed at that height (to save time and energy), O means a successful attempt, and X means a failed attempt. So, the winner passed at all heights up to and including 2.70 meters, succeeded on the first attempt at 2.85, 3.00, and 3.15 meters. This athlete was the only one who cleared 3.15 meters and thus won the competition. This athlete then failed three times at 3.30 meters: each athlete has three attempts at each height; three failures at one height means elimination from the competition.

The athletes in the next three lines had the exact same performance: success at 2.70 and 2.85 meters on the first attempt, and then three straight failed attempts at 3.00 meters. Because there is nothing to distinguish the three performances, the athletes are deemed to be tied.

The athletes in fifth and sixth place also cleared 2.85 meters, but on their second attempts. Therefore, they are behind the athletes who cleared 2.85 meters on the first attempt. Furthermore, the athlete in fifth place cleared 2.70 meters on the first attempt, while the athlete in sixth place needed two attempts. Similarly, the athletes in seventh and eighth place both cleared 2.70 meters; the tiebreaker is the number of attempts needed at 2.40 meters.

Ties can also happen in elite competition as well. This dramatically happened in the men’s high jump at the 2021 Summer Olympics and the women’s pole vault at the 2023 World Championships, where the top two competitors tied and decided to share the gold medal.

By contrast, at the 2024 Olympics, the top two competitors in the men’s high jump tied but decided to continue the competition with a jumpoff until there was one winner.

My apologies to any track and field experts if my description of the scoring wasn’t quite perfect.

Back to mathematics… and back to the scores. Why did the computer think that the number of points from jumps was 16.333333492279053 and not ?

There are two parts to the answer: (1) Computers store numbers in binary, and (2) they only store a finite number of binary digits.

Converting 16 into binary is easy: since , its representation in binary is 10000.

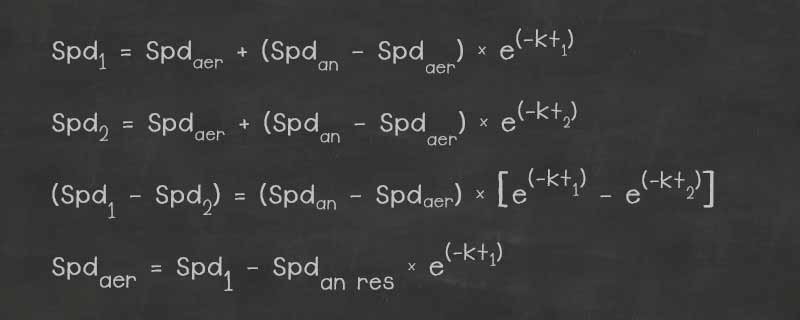

Converting into binary is more challenging, and perhaps I’ll write a separate post on this topic. This particular fraction can be found by using the formula for an infinite geometric series:

If we let , then we find

.

Said another way,

Combining the two results,

This is mathematically correct; however, computers use floating-point arithmetic only store a finite number of digits to represent any number. In this case, we can reverse-engineer to figure out how many digits are stored. In this case, after some trial and error, I found that 21 digits were apparently stored after the decimal point:

This is equivalent to the sum ; notice that the last fraction is basically rounding up in binary. Mathematica confirms that this sum matches the sum shown in the school’s team score:

So the computer showed far too many decimal places in the “Jumps” field, and it probably should’ve been programmed to show only two decimal places, like in the “Points” field.

I close by linking to this previous post on the 1991 Gulf War, describing why a similarly small error in approximating in binary tragically led to a bigger computational error that caused the death of 28 soldiers.