In my capstone class for future secondary math teachers, I ask my students to come up with ideas for engaging their students with different topics in the secondary mathematics curriculum. In other words, the point of the assignment was not to devise a full-blown lesson plan on this topic. Instead, I asked my students to think about three different ways of getting their students interested in the topic in the first place.

I plan to share some of the best of these ideas on this blog (after asking my students’ permission, of course).

This student submission comes from my former student Alyssa Dalling. Her topic, from Algebra II: finding the area of a square or rectangle.

A. What interesting (i.e., uncontrived) word problems using this topic can your students do now?

A fun way to engage students on the topic of solving systems of equations using matrices is by using real world problems they can actually understand. Below are some such problems that students can relate to and understand a purpose in finding the result.

- The owner of Campbell Florist is assembling flower arrangements for Valentine’s Day. This morning, she assembled one large flower arrangement and found it took her 8 minutes. After lunch, she arranged 2 small arrangements and 15 large arrangements which took 130 minutes. She wants to know how long it takes her to complete each type of arrangement.

(Idea and solution on http://www.ixl.com/math/algebra-1/solve-a-system-of-equations-using-augmented-matrices-word-problems )

- The Lakers scored a total of 80 points in a basketball game against the Bulls. The Lakers made a total of 37 two-point and three-point baskets. How many two-point shots did the Lakers make? How many three-point shots did the Lakers make?

(Idea and solution on http://www.algebra-class.com/system-of-equations-word-problems.html )

A. How could you as a teacher create an activity or project that involves your topic?

- For this topic, creating a fun activity would be one of the best ways to help students learn and explore solving systems of equations using matrices. One way in which this could be done is by creating a fun engaging activity that allows the students to use matrices while completing a fun task. The type of activity I would create would be a sort of “treasure hunt.” Students would have a question they are trying to find the solution for using matrices. They would solve the system of equations and use that solution to count to the letter in the alphabet that corresponds to the number they found. In the end, the solution would create different blocks of letters that the student would have to unscramble.

For Example: The top of the page would start a joke such as “What did the Zero say to the Eight?…

Solve and

using matrices.

To solve this, the student would put this information into a matrix and find the solution came out to be and

. They would count in the alphabet and see that the 12th letter was L and the 14th letter was N. Then at the bottom of their page, they would find where it said to write the letters for x and y such as below-

N __ __ __ __ __ L __! (Nice Belt!)

x a c z d z y w

E. How can technology be used to effectively engage students with this topic?

This activity would be used after students have learned the basics of putting a matrix into their calculator to solve. The class would be separated into small groups (>5 or more if possible with 2-3 kids per group) The rules are as follows: a group can work together to set up the equation, but each individual in the group had to come up to the board and write out their groups matrices and solution. The teacher would hand out a paper of 8-12 problems and tell the students they can begin. The first group to finish all the problems correctly on the board wins. There would be problems ranging from 2 variables to 4.

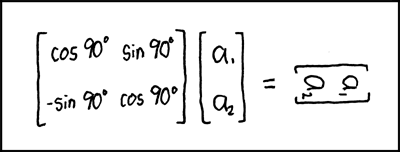

Ex: One of the problems could be and . The groups would have to first solve this on their paper using their calculator then the first person would come up to the board to write how they solved it-

Written on the board:

The technology of calculators allows this to be a fun and fast paced game. It will allow students to understand how to use their calculator better while allowing them to have fun while learning.