Many math majors don’t have immediate recall of the formula for an infinite geometric series. They often can remember that there is a formula, but they can’t recollect the details. While it’s I think it’s OK that they don’t have the formula memorized, I think is a real shame that they’re also unaware of where the formula comes from and hence are unable to rederive the formula if they’ve forgotten it.

In this post, I’d like to give some thoughts about why the formula for an infinite geometric series is important for other areas of mathematics besides Precalculus. (There may be others, but here’s what I can think of in one sitting.)

1. An infinite geometric series is actually a special case of a Taylor series. (See https://meangreenmath.com/2013/07/05/reminding-students-about-taylor-series-part-5/ for details.) Therefore, it would be wonderful if students learning Taylor series in Calculus II could be able to relate the new topic (Taylor series) to their previous knowledge (infinite geometric series) which they had already seen in Precalculus.

2. An infinite geometric series is also a special case of the binomial series , when

does not have to be a positive integer and hence Pascal’s triangle cannot be used to find the expansion.

3. Infinite geometric series is a rare case when an infinite sum can be found exactly. In Calculus II, a whole battery of tests (e.g., the Root Test, the Ratio Test, the Limit Comparison Test) are introduced to determine whether a series converges or not. In other words, these tests only determine if an answer exists, without determining what the answer actually is.

Throughout the entire undergraduate curriculum, I’m aware of only four types of series that can actually be evaluated exactly.

- An infinite geometric series with

- The Taylor series of a real analytic function. (Of course, an infinite geometric series is a special case of a Taylor series.)

- A telescoping series. For example, using partial fractions and cancelling a bunch of terms, we find that

- An infinite series that arises from Parseval’s theorem in Fourier analysis.

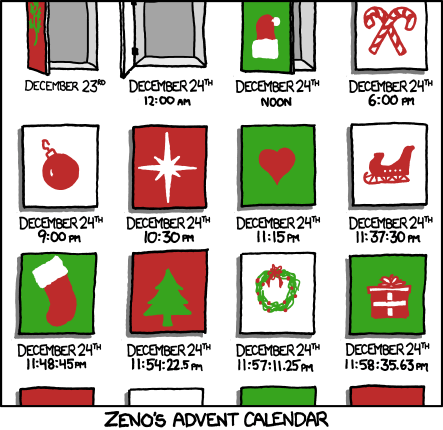

4. Infinite geometric series are essential for proving basic facts about decimal representations that we often take for granted.

- We can justify why

. See https://meangreenmath.com/2013/09/03/why-does-0-999-1-part-3/ for details.

- Along with the Direct Comparison Test, we can be used to justify why a decimal representation

actually converges and must correspond to a real number. See https://meangreenmath.com/2013/09/01/why-does-0-999-1-part-1/ for details.

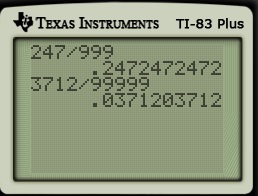

- We can prove that a fraction of the form

must have a repeating block of length

which contains the digits of

. See https://meangreenmath.com/2013/08/22/thoughts-on-17-and-other-rational-numbers-part-5/ for details.

- Going the other direction, we can also convert an repeating decimal representation into a fraction. See https://meangreenmath.com/2013/08/21/thoughts-on-17-and-other-rational-numbers-part-4/ for details.

- We can also find representations in other bases besides base 10. See https://meangreenmath.com/2013/08/17/calculator-errors-when-close-isnt-close-enough-part-2 for an example of a repeating binary representation.

5. Properties of an infinite geometric series are needed to find the mean and standard deviation of a geometric random variable, which is used to predict the number of independent trials needed before an event happens. This is used for analyzing the coupon collector’s problem, among other applications.