In Part 2 of this series, I discussed the process of converting a fraction into its decimal representation. In this post, I consider the reverse: starting with a decimal representation, and ending with a fraction.

Let me say at the onset that the process I’m about to describe appears to be a dying art. When I show this to my math majors who want to be high school teachers, roughly half have either not seen it before or else have no memory of seeing it before. (As always, I hold my students blameless for the things that they were simply not taught at a younger age, and part of my job is repairing these odd holes in their mathematical backgrounds so that they’ll have their best chance at becoming excellent high school math teachers.) I’m guessing that this algorithm is a dying art because of the ease and convenience of modern calculators.

So let me describe how I describe this procedure to my students. To begin, suppose that we’re given a repeating decimal like  . How do we change this into a decimal? Let’s call this number

. How do we change this into a decimal? Let’s call this number  .

.

I’m now about to do something that, if you don’t know what’s coming next, appears to make no sense. I’m going to multiply  by

by  . Students often give skeptical, quizzical, and/or frustrated looks about this non-intuitive next step… they’re thinking, “How would I ever have thought to do that on my own?” To allay these concerns, I explain that this step comes from the patented Bag of Tricks. Socrates gave the Bag of Tricks to Plato, Plato gave it to Aristotle, it passed down the generations, my teacher taught the Bag of Tricks to me, and I teach it to my students. Multiplying by

. Students often give skeptical, quizzical, and/or frustrated looks about this non-intuitive next step… they’re thinking, “How would I ever have thought to do that on my own?” To allay these concerns, I explain that this step comes from the patented Bag of Tricks. Socrates gave the Bag of Tricks to Plato, Plato gave it to Aristotle, it passed down the generations, my teacher taught the Bag of Tricks to me, and I teach it to my students. Multiplying by  on the next step is absolutely not obvious, unless you happen to know via clairvoyance what’s going to come next.

on the next step is absolutely not obvious, unless you happen to know via clairvoyance what’s going to come next.

Anyway, let’s write down  and also

and also  .

.

Notice that the decimal parts of both  and

and  are the same. Subtracting, the decimal parts cancel, leaving

are the same. Subtracting, the decimal parts cancel, leaving

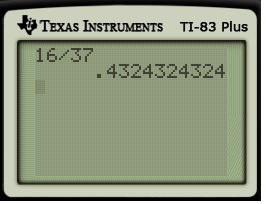

or

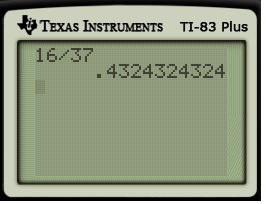

In my experience, most students — even senior math majors who have taken a few theorem-proof classes and hence are no dummies — are a little stunned when they see this procedure for the first time. To make this more real and believable to them, I then ask them to pop out their calculators to confirm that this actually worked. (Indeed, many students need this confirmation to be psychologically sure that it really did work.)

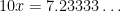

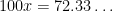

Then I ask my students, why did we multiply by  ? They’ll usually give the correct answer: so that the decimal parts will cancel. My follow-up question is, what should we do if the decimal is

? They’ll usually give the correct answer: so that the decimal parts will cancel. My follow-up question is, what should we do if the decimal is  ? They’ll usually respond that we should multiply by

? They’ll usually respond that we should multiply by  or, in general, by

or, in general, by  , where

, where  is the length of the repeating block.

is the length of the repeating block.

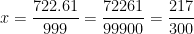

This strategy, of course, works for $0.\overline{142857}$, eventually yielding

after cancellation.

The same procedure works for decimal expansions with a delay, like  . This time, I’ll ask them how we should go about changing this into a fraction. I usually get at least one of three responses. I love getting multiple responses, as this gives the students a chance to came the “different” answers, compare the different strategies, and

. This time, I’ll ask them how we should go about changing this into a fraction. I usually get at least one of three responses. I love getting multiple responses, as this gives the students a chance to came the “different” answers, compare the different strategies, and

Answer #1. Multiply  by

by  since the repeating pattern starts at the 3rd decimal place.

since the repeating pattern starts at the 3rd decimal place.

Answer #2. Multiply  by

by  since the repeating block has length 1.

since the repeating block has length 1.

Answer #3. First multiply  by 100 to get rid of the delay. Then multiply

by 100 to get rid of the delay. Then multiply  by an extra

by an extra  since the repeating block has length 1.

since the repeating block has length 1.

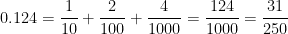

The above discussion concerned repeating decimals. For completeness, converting terminating decimals into a fraction is easy. For example,

One more thought. The concept behind Part 2 of this series shows that a rational number of the form  , where both

, where both  and

and  are integers, must have either a terminating decimal expansion or else a repeating decimal expansion (possibly with a delay). In this post, we went the other direction. Therefore, we have the basis for the following theorem.

are integers, must have either a terminating decimal expansion or else a repeating decimal expansion (possibly with a delay). In this post, we went the other direction. Therefore, we have the basis for the following theorem.

Theorem. A number  is rational if and only if it has either a terminating decimal expansion or else a repeating decimal expansion.

is rational if and only if it has either a terminating decimal expansion or else a repeating decimal expansion.

The contrapositive of this theorem is perhaps intuitively obvious.

Theorem. A number  is irrational if and only if it has a non-terminating and non-repeating decimal expansion.

is irrational if and only if it has a non-terminating and non-repeating decimal expansion.

In my experience, most students absolutely believe both of these theorems. For example, most students believe that  has a decimal expansion that neither terminates nor repeats. That said, most math majors are surprised to discover that it does take quite a bit of work — like a formal write-up of Parts 2 and 3 of this series — to actually prove this statement from middle-school mathematics.

has a decimal expansion that neither terminates nor repeats. That said, most math majors are surprised to discover that it does take quite a bit of work — like a formal write-up of Parts 2 and 3 of this series — to actually prove this statement from middle-school mathematics.

in the following picture (this picture is taken from http://thinkzone.wlonk.com/MathFun/Triangle.htm):

without clicking on any of these links… a certain trick out of the patented Bag of Tricks is required to solve this problem using only geometry (as opposed to the Law of Cosines and the Law of Sines). I have a story that I tell my students about the patented Bag of Tricks: Socrates gave the Bag of Tricks to Plato, Plato gave it to Aristotle, it passed down the generations, my teacher taught the Bag of Tricks to me, and I teach it to my students. In the same post, Math With Bad Drawings has a nice discussion about pedagogical aspects of this problem concerning when a “trick” becomes a “technique”.