In this series of posts, I explore properties of complex numbers that explain some surprising answers to exponential and logarithmic problems using a calculator (see video at the bottom of this post). These posts form the basis for a sequence of lectures given to my future secondary teachers.

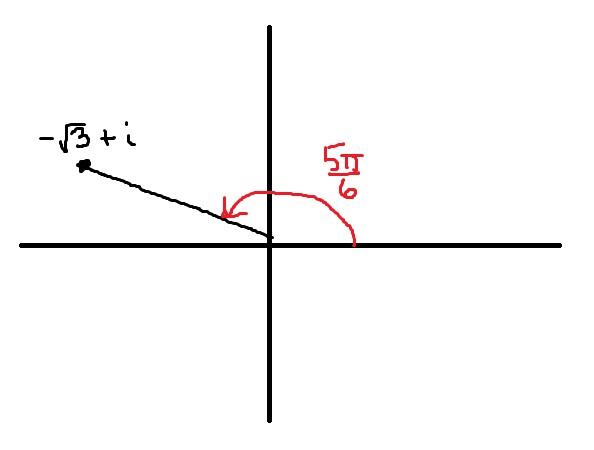

To begin, we recall that the trigonometric form of a complex number is

where and

, with

in the appropriate quadrant. As noted before, this is analogous to converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

There’s a shorthand notation for the right-hand side () that I’ll justify later in this series.

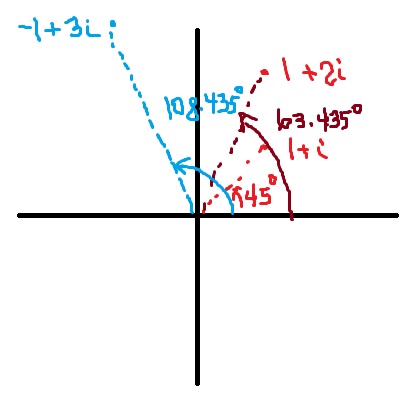

Why is this important? When students first learn to multiply complex numbers like and

, they are taught to just distribute (or, using the nomenclature that I don’t like, FOIL it out):

.

The trigonometric form of a complex number permits a geometric interpretation of multiplication, given in the following theorem.

Theorem. .

Proof. As above, we distribute (except for the and

terms):

.

When actually doing this in class, the big conceptual jump for students is the last step. So I make a big song-and-dance routine out of this:

Cosine of the first times cosine of the second minus sine of the first times sine of the second… where have I seen this before?

The idea is for my students to search deep into their mathematical memories until they recall the appropriate trig identity.

For the original multiplication problem, we see that

Therefore, the product of $1+i$ and $1+2i$ will be a distance of $\sqrt{2} \cdot \sqrt{5} = \sqrt{10}$ from the origin, and the angle from the positive real axis will be . Indeed,

.

For completeness, here’s the movie that I use to engage my students when I begin this sequence of lectures.