Category: Humor

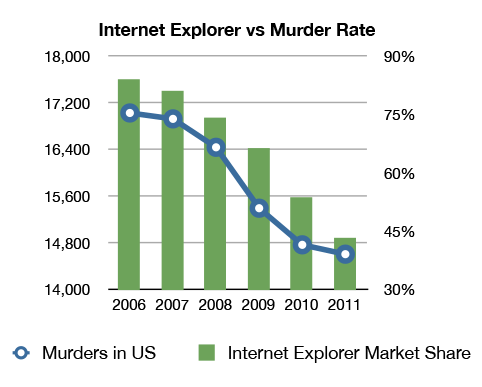

Correlation and causation

In my statistics classes, I try to emphasize to student that correlation is not the same thing as causation. Still, the following two graphs are absolutely brilliant.

Number of Pirates vs. Global Warming

Conclusion: If you want to stop global warming, we should all become pirates.

Sources: http://www.scq.ubc.ca/wp-content/piracy01.gif and http://iwastesomuchtime.com/on/?i=64193

Good use of hexadecimal

This morning, I had the pleasant thought that I still am only 29 years old… as long as I use hexadecimal.

Epsilon

Years ago, when I taught calculus, I’d usually include the following extra credit question on the first exam: “In the small box, write a good value for . A valid answer gets 4 points; the smallest answer in the class will get 5 points.” It was basically free extra credit… any positive number would work, but it was a (hopefully) fun way for students to be a little competitive in coming up with small positive numbers, which is the intuitive meaning of

in mathematics. (I still remember when my high school math teacher was giving me directions to a restaurant, concluding “You’ll know you’re within

of the restaurant when you see the signs for Such-and-Such Mall.”)

Most students volunteered something like or

. Except for one particularly gutsy student who wrote, “The probability that Dr. Q gets a date on Friday night.” For sheer nerve, he got the 5 points that year.

Also getting 5 points that year was the best answer of the class: “Let be the smallest answer that anyone else wrote. Then

.” That was especially clever from a calculus student, as that’s the essence of a fairly common technique when writing proofs in real analysis.

A good clean joke

Two algebra teachers are on a plane. Shortly after reaching cruising altitude, one of the engines conks out. However, the flight attendant announces that the plane has three other engines. However, instead of needing 3 hours to fly to their destination on 4 engines, it will now take 4 hours to fly on 3 engines.

A little while later, another engine goes out. Never fear, says the flight attendant: the plane can fly on two engines. Unfortunately, the length of the flight has now increased to 6 hours.

Later still, a third engine fails. Not to worry, says the flight attendant. The plane can fly on only one engine. But the flight will now last 12 hours.

So one algebra teacher says to the other, “I really hope that last engine doesn’t go out, or else we’ll be up here forever!”

Interdisciplinary studies (part 2)

A provost complains to the physics faculty about how much money it costs for labs, lasers, technical staff, and other associated costs of doing their work. “Why can’t you be more like the Math Department?” asks the provost. “All they need is money for pencils, paper, and a wastebasket. Or better still, you could be like the Philosophy Department. All they need is money for pencils and paper.”

Bumper sticker

How not to give a presentation

I doodled this list during a particularly grueling workshop presentation:

HOW NOT TO CONDUCT A TRAINING WORKSHOP

- Assume your audience consists entirely of peer reviewers judging the suitability of your presentation for publication.

- Make sure that every facet and angle of the theoretical and philosophical underpinnings of your presentation are covered.

- Present a thoroughly detailed and annotated literature review of all prior results.

- Design all PowerPoint slides in 10-point font or less.

- Present all quantitative results in at least two different useless graphical formats, courtesy of the fun charts that Microsoft Excel will let you make.

- Create multiple acronyms and use them aggressively.

- Devote the most amount of time to the most difficult topics and processes that only a select few will be asked to perform.

- Name-drop the top brass.

- Demonstrate complicated software without providing notes for the audience’s future reference.

- Emphasize how much the new process costs, so that everyone fully comprehends how importance it is that the new process doesn’t fail.

Dissertations

I first saw this gem in the delightful book Absolute Zero Gravity: Science Quotes, Jokes and Anecdotes.

A little rabbit was sitting in a field, scribbling on a pad of paper, when a fox came along. “What are you doing, little rabbit?”

“I’m working on my dissertation,” said the rabbit.

“Really?” said the fox. “And what is your topic?”

“Oh, the topic doesn’t matter,” said the rabbit.

“No, tell me,” begged the fox.

“If you must know,” said the rabbit, “I’m advancing a theory that rabbits can eat many quite large animals – including, for instance, foxes.”

“Surely you have no experimental evidence for that,” scoffed the fox.

“Yes, I do,” said the rabbit, “and if you’d like to step inside this cave for a moment I’ll be glad to show you.” So the fox followed the rabbit into the cave. About half an hour passed. Then the rabbit came back out, brushing a tuft of fox fur off his chin, and began once more to scribble on his pad of paper.

News spreads quickly in the forest, and it wasn’t long before a curious wolf came along. “I hear you’re writing a thesis, little rabbit,” said the wolf.

“Yes,” said the rabbit, scribbling away.

“And the topic?” asked the wolf.

“Not that it matters, but I’m presenting some evidence that rabbits can eat larger animals – including, for example, wolves.” The wolf howled with laughter. “I see you don’t believe me,” said the rabbit. “Perhaps you would like to step inside this cave and see my experimental apparatus.”

Licking her chops, the wolf followed the rabbit into the cave. About half an hour passed before the rabbit came out of the cave with his pad of paper, munching on what looked like the end of a long gray tail.

Then along came a big brown bear. “What’s this I hear about your thesis topic?” he demanded.

“I can’t imagine why you all keep pestering me about my topic,” said the rabbit irritably. “As if the topic made any difference at all.”

The bear sniggered behind his paw. “Something about rabbits eating bigger animals was what I heard – and apparatus inside the cave.”

“That’s right,” snapped the rabbit, putting down his pencil. “And if you want to see it I’ll gladly show you.” Into the cave they went, and a half hour later the rabbit came out again picking his teeth with a big bear claw.

By now all the animals in the forest were getting nervous about the rabbit’s project, and a little mouse was elected to sneak up and peek into the cave when the rabbit’s back was turned. There she discovered that the mystery of the rabbit’s thesis had not only a solution but also a moral. The mystery’s solution is that the cave contained an enormous lion. And the moral is that your thesis topic really doesn’t matter – as long as you have the right thesis advisor.

Multiple choice

I had a good chuckle at the following photo.

Here’s a thought bubble if you’d like to think about it before I reveal the answer.

You’d think that, since there are four possible answers, that you should answer 25%. However, there are two choices for 25%, so the chance of picking 25% as your answer is 2/4, or 50%. But there’s only one way to answer 50%, so the answer should be 1/4, or 25%. To quote “The King and I,” et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

The correct answer, of course, is adding a fifth option: E) 20%.