Category: Humor

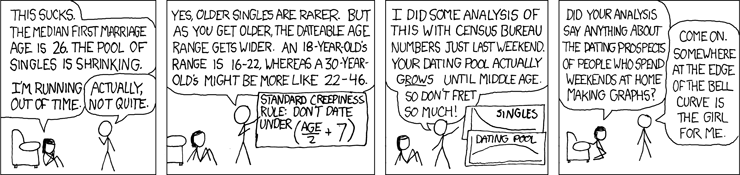

Dating pools

Source: http://www.xkcd.com/314/

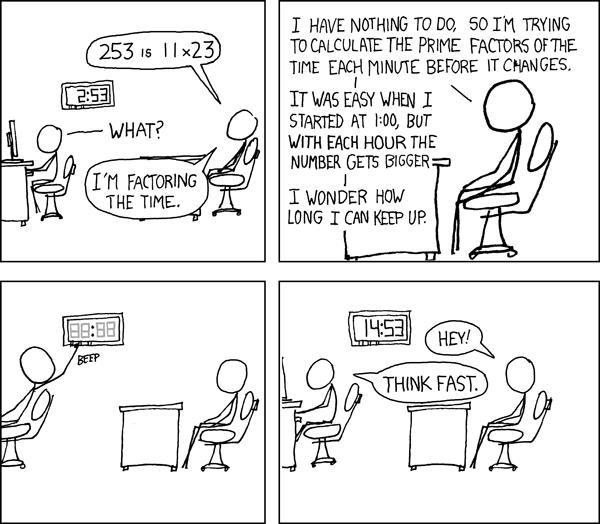

Factoring the time

True story: one way that I commit large numbers to (hopefully) short-term memory is by factoring. If I take the time to factor a big number, then I can usually remember it for a little while.

This approach has occasional disadvantages. For example, I now have stuck in my brain the completely useless information that, many years ago, my seat at a Texas Rangers ballgame was somewhere in Section 336 (which is ).

Source: http://www.xkcd.com/247/

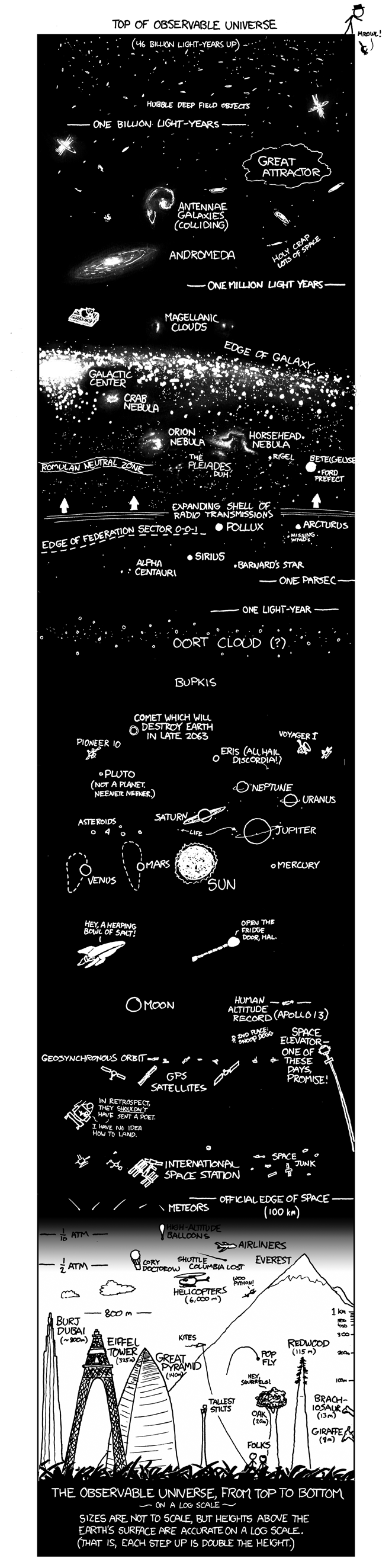

Height

I’m about to do a series of posts concerning square roots and logarithms. So I thought that this picture would be an appropriate introduction to the topic. (One of these days, I’ll spring for the wall poster version of this picture to hang in my office.)

Source: http://www.xkcd.com/482/

Arctangents and showmanship

This story comes from Fall 1996, my first semester as a college professor. I was teaching a Precalculus class, and the topic was vectors. I forget the exact problem (believe me, I wish I could remember it), but I was going over the solution of a problem that required finding . I told the class that I had worked this out ahead of time, and that the approximate answer was

. Then I used that angle for whatever I needed it for and continued until obtaining the eventual solution.

(By the way, I now realize that I was hardly following best practices by computing that angle ahead of time. Knowing what I know now, I should have brought a calculator to class and computed it on the spot. But, as a young professor, I was primarily concerned with getting the answer right, and I was petrified of making a mistake that my students could repeat.)

After solving the problem, I paused to ask for questions. One student asked a good question, and then another.

Then a third student asked, “How did you know that was

?

Suppressing a smile, I answered, “Easy; I had that one memorized.”

The class immediately erupted… some with laughter, some with disbelief. (I had a terrific rapport with those students that semester; part of the daily atmosphere was the give-and-take with any number of exuberant students.) One guy in the front row immediately challenged me: “Oh yeah? Then what’s ?

I started to stammer, “Uh, um…”

“Aha!” they said. “He’s faking it.” They start pulling out their calculators.

Then I thought as fast as I could. Then I realized that I knew that , thanks to my calculation prior to class. I also knew that

since the graph of

has a vertical asymptote at

. So the solution to

had to be somewhere between

and

.

So I took a total guess. “,” I said, faking complete and utter confidence.

Wouldn’t you know it, I was right. (The answer is about .)

In stunned disbelief, the guy who asked the question asked, “How did you do that?”

I was reeling in shock that I guessed correctly. But I put on my best poker face and answered, “I told you, I had it memorized.” And then I continued with the next example. For the rest of the semester, my students really thought I had it memorized.

To this day, this is my favorite stunt that I ever pulled off in front of my students.

Please move the deer crossing

Nearly all of the posts on this blog lie somewhere in the union (and often in the intersection) of mathematics and education, discussing ways of deepening content knowledge and imparting that knowledge to students.

This is not one of those posts.

However, if I ever need to lighten the mood with my students, this never fails to get a laugh.

And, in case if you’re wondering if the above phone call was a fake, here’s the rest of the story:

Certainty

Source: http://www.xkcd.com/263/

Math T-shirts

The following are the three finalists for the T-shirt contest sponsored by the Mathematical Association of America.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10151715596230419.1073741825.153302905418&type=1

Source: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10151715596230419.1073741825.153302905418&type=1

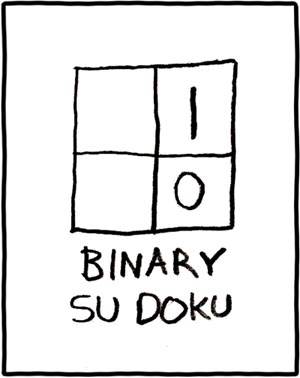

Binary sudoku

After a week of posts on Taylor series, I thought something on the lighter side would be appropriate.

Source: http://www.xkcd.com/74/

Video pranks in class

Dr. Matthew Weathers is an assistant professor of Mathematics and Computer Science at Biola University and also a world-class showman. Here are some of his biggest hits (often for Halloween or April Fools’ Day). Enjoy. (If you’re interested, you can find more at his YouTube page, http://www.youtube.com/user/MDWeathers/videos?sort=p&view=0&flow=grid.