In this series, I’m compiling some of the quips and one-liners that I’ll use with my students to hopefully make my lessons more memorable for them.

At many layers of the mathematics curriculum, students learn about that various functions can essentially commute with each other. In other words, the order in which the operations is performed doesn’t affect the final answer. Here’s a partial list off the top of my head:

- Arithmetic/Algebra:

. This of course is commonly called the distributive property (and not the commutative property), but the essential idea is that the same answer is obtained whether the multiplications are performed first or if the addition is performed first.

. This of course is commonly called the distributive property (and not the commutative property), but the essential idea is that the same answer is obtained whether the multiplications are performed first or if the addition is performed first.

- Algebra: If

, then

, then  .

.

- Algebra: If

and

and  is any real number, then

is any real number, then  .

.

- Precalculus:

.

.

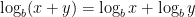

- Precalculus:

.

.

- Calculus: If

is continuous at an interior point

is continuous at an interior point  , then

, then  .

.

- Calculus: If

and

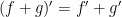

and  are differentiable, then

are differentiable, then  .

.

- Calculus: If

is differentiable and

is differentiable and  is a constant, then

is a constant, then  .

.

- Calculus: If

and

and  are integrable, then

are integrable, then  .

.

- Calculus: If

is integrable and

is integrable and  is a constant, then

is a constant, then  .

.

- Calculus: If

is integrable,

is integrable,  .

.

- Calculus: For most differentiable function

that arise in practice,

that arise in practice,  .

.

- Probability: If

and

and  are random variables, then

are random variables, then  .

.

- Probability: If

is a random variable and

is a random variable and  is a constant, then

is a constant, then  .

.

- Probability: If

and

and  are independent random variables, then

are independent random variables, then  .

.

- Probability: If

and

and  are independent random variables, then

are independent random variables, then  .

.

- Set theory: If

,

,  , and

, and  are sets, then

are sets, then  .

.

- Set theory: If

,

,  , and

, and  are sets, then

are sets, then  .

.

However, there are plenty of instances when two functions do not commute. Most of these, of course, are common mistakes that students make when they first encounter these concepts. Here’s a partial list off the top of my head. (For all of these, the inequality sign means that the two sides do not have to be equal… though there may be special cases when equality happens to happen.)

- Algebra:

if

if  . Important special cases are

. Important special cases are  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

- Algebra/Precalculus:

. I call this the third classic blunder.

. I call this the third classic blunder.

- Precalculus:

.

.

- Precalculus:

,

,  , etc.

, etc.

- Precalculus:

.

.

- Calculus:

.

.

- Calculus

- Calculus:

.

.

- Probability: If

and

and  are dependent random variables, then

are dependent random variables, then  .

.

- Probability: If

and

and  are dependent random variables, then

are dependent random variables, then  .

.

All this to say, it’s a big deal when two functions commute, because this doesn’t happen all the time.

I wish I could remember the speaker’s name, but I heard the following one-liner at a state mathematics conference many years ago, and I’ve used it to great effect in my classes ever since. Whenever I present a property where two functions commute, I’ll say, “In other words, the order of operations does not matter. This is a big deal, because, in real life, the order of operations usually is important. For example, this morning, you probably got dressed and then went outside. The order was important.”

I wish I could remember the speaker’s name, but I heard the following one-liner at a state mathematics conference many years ago, and I’ve used it to great effect in my classes ever since. Whenever I present a property where two functions commute, I’ll say, “In other words, the order of operations does not matter. This is a big deal, because, in real life, the order of operations usually is important. For example, this morning, you probably got dressed and then went outside. The order was important.”