The following problem appeared in Volume 96, Issue 3 (2023) of Mathematics Magazine.

Let

be arbitrary events in a probability field. Denote by

the event that at least

of

occur. Prove that

.

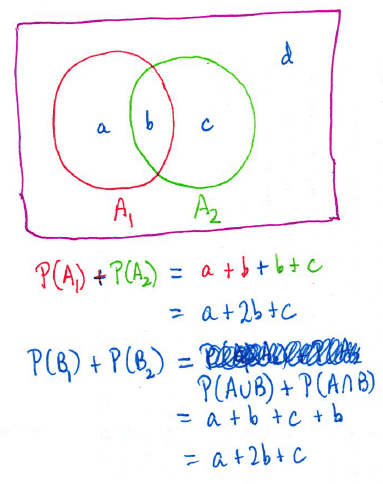

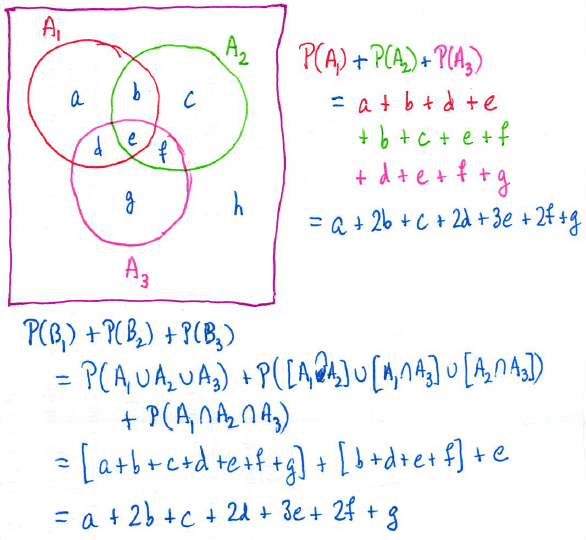

I’ll admit when I first read this problem, I didn’t believe it. I had to draw a couple of Venn diagrams to convince myself that it actually worked:

Of course, pictures are not proofs, so I started giving the problem more thought.

I wish I could say where I got the inspiration from, but I got the idea to define a new random variable to be the number of events from

that occur. With this definition,

becomes the event that

, so that

At this point, my Spidey Sense went off: that’s the tail-sum formula for expectation! Since is a non-negative integer-valued random variable, the mean of

can be computed by

.

Said another way, .

Therefore, to solve the problem, it remains to show that is also equal to

. To do this, I employed the standard technique from the bag of tricks of writing

as the sum of indicator random variables. Define

Then , so that

.

Equating the two expressions for , we conclude that

, as claimed.

One thought on “Solving Problems Submitted to MAA Journals (Part 4)”