In this series, I’m discussing how ideas from calculus and precalculus (with a touch of differential equations) can predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit and thus confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The origins of this series came from a class project that I assigned to my Differential Equations students maybe 20 years ago.

As part of our derivation, we’ll need to use the fact that, in polar coordinates, the graph of

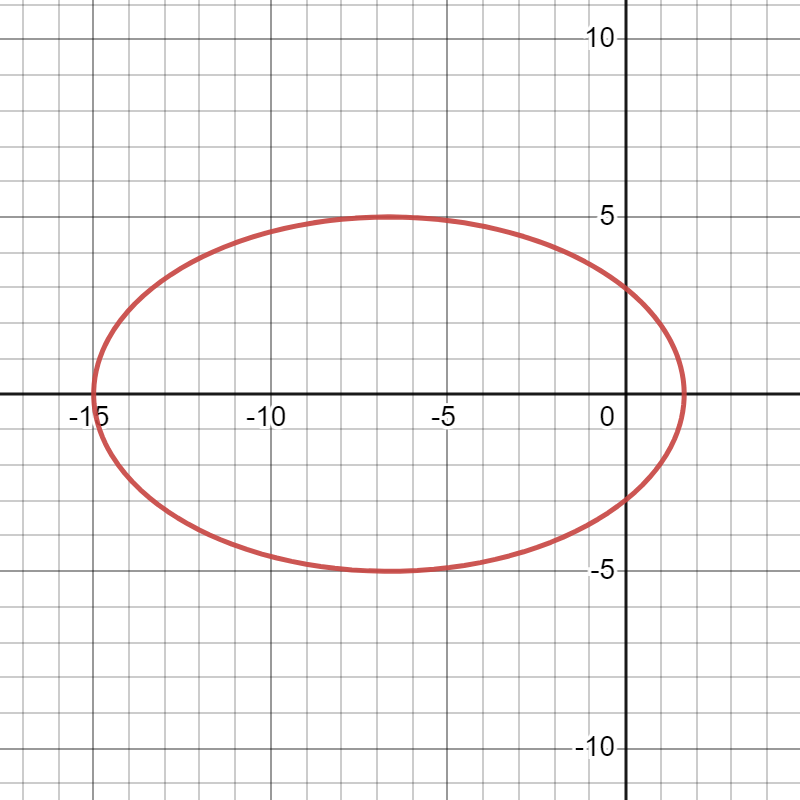

turns out to be an ellipse if , with the origin at one focus.

We now prove this. Clearing the denominator, we obtain

.

Switching to rectangular coordinates, this becomes

Since we assumed that , we have

so that

.

Therefore, this matches the usual form of an ellipse in rectangular coordinates

,

where the center of the ellipse is located at

,

the semi-major axis is horizontal with length

,

and the semi-minor axis is vertical with length

.

Furthermore, the distance of the foci from the center of the ellipse satisfies the equation

,

so that

From this, we derive two nice properties of the ellipse. First, looking back on previous work, we see that . Therefore, since the foci of the ellipse are distance

away from the center along the major axis, we conclude that one focus of the ellipse is located at

, or

. That is, the origin is one focus of the ellipse. (For the little it’s worth, the other focus is located at

.

Second, the eccentricity of the ellipse is defined to be the ratio . This is now easily computed:

.

In other words, the letter was well-chosen to represent the eccentricity of the ellipse.

For what it’s worth, here’s an alternate derivation of the formulas for and

. For this ellipse, the planet’s closest approach to the Sun occurs at

:

,

and the planet’s further distance from the Sun occurs at :

.

Therefore, the length of the major axis of the ellipse is the sum of these two distances:

.

Since , we can also compute

:

One thought on “Confirming Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity With Calculus, Part 2b: Ellipses and Polar Coordinates”