If the universe consisted of only Mercury and the sun, Mercury’s trajectory would trace the same ellipse over and over again. However, there are seven other planets in the solar system (not to mention the dwarf planets), and these planets tug and nudge the orbit of Mercury ever so slightly. (For what it’s worth, similar nudges in the orbit of Uranus led to the discovery of Neptune in 1846.)

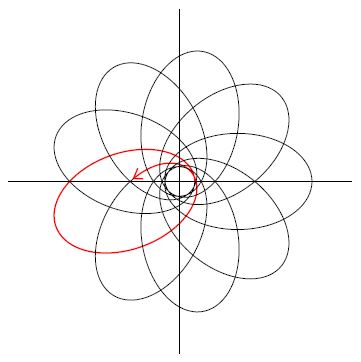

The practical effect of these nudges is that the orbit of Mercury precesses, or rotates like a spiral. The figure below shows the (greatly exaggerated) effect of precession on a planet’s otherwise elliptical orbit. In the figure, each perihelion is precessed by an angle of . After nine orbits, the planet returns to its original position.

Since the planets are much smaller than the sun and are further away from the Sun than Mercury, this precession is very small. However, this effect can be measured. Every century, the perihelion of Mercury precesses by 574” of arc (roughly a sixth of a degree).

Newton’s Law of Gravitation can be used to calculate the amount of the precession of Mercury; however, they predict a precession of only 531” of arc per century. This discrepancy between observation and prediction was first observed in 1845 and was, for a long time, the outstanding unresolved difficulty in Newtonian physics.

Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which was published seventy years later in 1915, exactly accounts for the missing 43” per century (within the tolerances of observational error). This was the first physical confirmation of general relativity. Furthermore, general relativity predicted that the orbit of Venus also precesses, but by only about 9” of arc per century. This small discrepancy was unobservable in 1915 but was confirmed in 1960. (While not logically necessary, that’s certainly indicative of an accurate scientific theory… not that it merely explains the world but it makes a prediction that is currently unobservable.)

In this series, which might take me a few months to complete, I’m going to explore how to predict the precession in Mercury’s orbit — i.e., confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity — using tools only from calculus and precalculus. I first introduced these ideas as a class project for my Differential Equations students maybe 20 years ago. As we’ll see, in a couple spots, ideas from first-semester differential equations can make the steps more rigorous. However, pretty much this whole series should be accessible to a good calculus student.

I should say at the outset that none of the mathematics in this series is particularly original with me. I gladly acknowledge that I first learned the ideas in this series as an undergraduate, when I took an upper-level physics course in mechanics. In particular, pretty much all of the ideas in this series can be found in the textbook Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems, by S. T. Thornton and J. B. Marion (Brooks Cole, New York, 2003). If I’ve made any contribution, it’s the scaffolding of these ideas to make them accessible to students who won’t be taking (or haven’t yet taken) physics courses beyond the traditional first-year sequence.

One thought on “Confirming Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity With Calculus, Part 1a: Introduction”